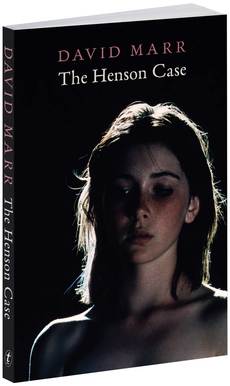

Book review of The Henson Case by David Marr (Text Publishing)

Published in Source

Summer 2009, Issue 59

What is an appropriate photograph of a naked child? Who may be permitted to create it? Where might it be viewed? Who should be allowed to look at it? Definitions of art and pornography are never more contested as when discussions based on these kinds of questions are played out in the public arena. In recent years artists such as Tierney Gearnon, Nan Goldin, David Hamilton, Sally Mann, Robert Mapplethorpe, Graham Ovenden, Annelies Strba and Jock Sturges have all sparked controversy, debate and in some cases legal inquiry, for exhibiting photographs of naked children. It is a situation that seems to arise perennially and often runs a similar course. An artist exhibits work featuring a naked child and complaints are made; sensational reports feature in the media and the work is investigated by authorities; various public figures propagandize on the issue; fever pitch ensues the artist in relation to issues of pornography, paedophilia, censorship and the ‘protection’ of childhood.

The Henson Case by David Marr examines a recent example of this turn of events involving the Australian artist Bill Henson. In May 2008 an exhibition by Henson at the highly regarded Sydney gallery Roslyn Oxley9 was investigated by the police before opening to the public. It was shut down on the grounds of ‘inquiry in to the legality of the images’ and their possible pornographic representation of children, and several works were confiscated. The police then conducted further investigations of Henson’s work in some of the country’s most important public collections of art, including the National Gallery of Australia. The exhibition closure and investigations were extensively reported in the Australian national media with many prominent cultural and political figures making their views heard on the issue. Most notably the Australian Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, who remarked on national television that Henson’s work was “absolutely disgusting”, that it had “no artistic merit” and that “kids deserve to have the innocence of their childhood protected.”

Marr opens The Henson Case with a firsthand account of an editorial meeting of the Sydney Morning Herald. At this meeting an opinion piece was planned on the sexualisation of young girls using Henson’s forthcoming exhibition as a newshook. Marr observes that effectively it was this column and a vociferous talkback radio show encouraging listeners to view Henson’s work on the internet and lodge complaints, which led to the closure of the exhibition. He goes on to chronologically chart and consider the course of the subsequent media activity, police investigations, and the crisis management employed by Henson, incorporating eye-witness reporting and accounts derived from interviews with various sources. Including the parent of the young model depicted in the confiscated images, members of the police force, journalists, child abuse campaigners and Bill Henson himself.

The photographs that were confiscated are portraits of a 12 year old girl. She is depicted naked in swoon-like poses, her body appearing to emerge out of a black background. The girl’s budding breasts and pubis are dimly visible in some of the images. Her posture and facial expression do not appear to be overtly sexual, nor does she mimic an expression of adult sexuality. However the chiaroscuro of the controlled lighting used by Henson to illuminate her naked body might be interpreted as imparting a sensuous or provocative tone to the imagery.

Bill Henson is one of Australia’s most esteemed living visual artists. He was was given his first solo show in 1975 when just 18 years of age at the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia’s oldest and arguably most important public art institution. For over thirty years he has created a prolific body of work that predominantly depicts aestheticized imagery of young people juxtaposed with architectural studies and landscapes. Henson’s work is often described as being thematically preoccupied with metaphoric associations of light and dark, and the transitory state of adolescence and human existence. He has also come under much criticism for what might be read as the disempowered representation of women and young people proffered in his imagery. Often his models are naked or semi-clothed, covered in blood, dirt or sweat and pictured in postures suggestive of the aftermath of drug use, sex or violence. On why he works with children and adolescents, Henson has said that they are “the most effective vehicle for expressing ideas about humanity and vulnerability.”

While considered critical readings around the ethics of representation may be applied to Henson’s work, the extreme acts of confiscation, police investigation of the country’s art museum collections and the Prime Minister’s commentary on national television have been perceived by many as an objectionable form of censorship. Especially in light of a decision made in the aftermath of the affair by the Australian Government’s arts funding and advisory body, The Australia Council, to “develop a set of protocols that address the depiction of children in artworks, exhibitions and publications that receive government funding… to help artists who work with children to do so with proper care, sensitivity and responsibility.”

In providing an account of the machinations of the media and the spruiking of politicians and campaigners, and the symbiotic play of the two, The Henson Case presents an insightful snapshot of the manufacture of public anxiety around the issue of photographic representation of naked children. One of the most salient points raised by Marr in relation to this is how most of the people who made public comment about the images hadn’t actually seen Henson’s work in an uncensored form. The presentation of the photographs obscured by provocative cropping, pixilation and black bars essentially transformed the images into something significantly different to the actual works of art presented in the gallery. The Henson Case may also serve to historicise Bill Henson’s practice in terms of the ethical considerations around the issue of the agency of the young people he works with. This is an aspect of Henson’s practice that has come under much critical speculation in the past. Marr includes several positive testimonies by Henson’s models of giving their fully informed consent in relation to working with Henson.

Western civilization has always relished the bodies of young people and artists will carry on producing representations of naked children. The debate over what makes these representations ‘art’ or ‘porn’ will also certainly continue. It is a discussion that taps in to the core of society’s ever-increasing paranoia about the sexuality of children. David Marr’s The Henson Case may go some way to direct this debate toward a calm and more nuanced conversation that incorporates another set of questions that consider the source of this anxiety. What constitutes the ‘sexualisation’ of children? Why are we keen to ignore a child’s sensual or sexual experience of their own body? Why can’t we look at naked young people without a sense of shame or indecency? How can we include the voices of children in this discussion?

Anthony Luvera