I first travelled to Belfast in November 2006. By that time I had spent almost six years compiling photographs made by homeless people living in London. Finding myself in a position of guardian to a growing collection of negatives, photographs and ephemera created by over 250 people, I was uncertain as to whether this material was best considered a record of my investigations into representation or if the collection should somehow be manifested as a public archive. In beginning to address this question I spent time researching community archives and photography projects set up by individuals and grassroots organizations across the UK since the early 1970s, and I became particularly interested in Belfast Exposed Photography. The early history of Belfast Exposed, their archive and the organization’s continued critical engagement with socially and politically motivated photography chimed with my interests in rethinking documentary photography, the ethics of representation and collaboration. So when Karen Downey of Belfast Exposed extended an invitation to undertake a commission, this gave me an opportunity to further my research into their collection and to make a new body of work with homeless people living in Belfast.

In Belfast I made contact with two homeless support services. The Simon Community provided me with a meeting room in South Belfast for a short time, after which I continued working at The Welcome Organization in West Belfast. The ‘Welcome Centre’ was an important hub for a tight-knit community of people from all parts of Belfast who had found themselves without permanent accommodation for many different reasons. The drop-in centre pulsed with a constant stream of people milling through, shouts for “another tea or coffee?” and a television that blared from the moment the doors opened early in the morning until the last person left around midnight, seven days a week. With the warm hospitality of Joe McGuiggan, the founder of the centre, calling everyone to sit down to a three-course meal, being in the Welcome Centre had something of the embrace of an extended family at mealtime. I helped staff in the kitchen prepare and serve lunch and dinner, and I began to meet people.

When opportunities arose, I told the people I met about my work with photography. I explained that I had been collecting and making photographs with homeless people living in London and that I had come to Belfast to consider what to do with this collection by exploring the Belfast Exposed archive, and to create similar work with homeless people living in Belfast. I answered questions and invited those who were interested to take cameras away and to meet with me regularly to discuss the photographs they had made, encouraging all of the participants to photograph the things that interested them. Some people made photographs of their friends, family, special places and events, while others had more idiosyncratic uses for the camera in documenting their point of view, experience or memories of living in Belfast.

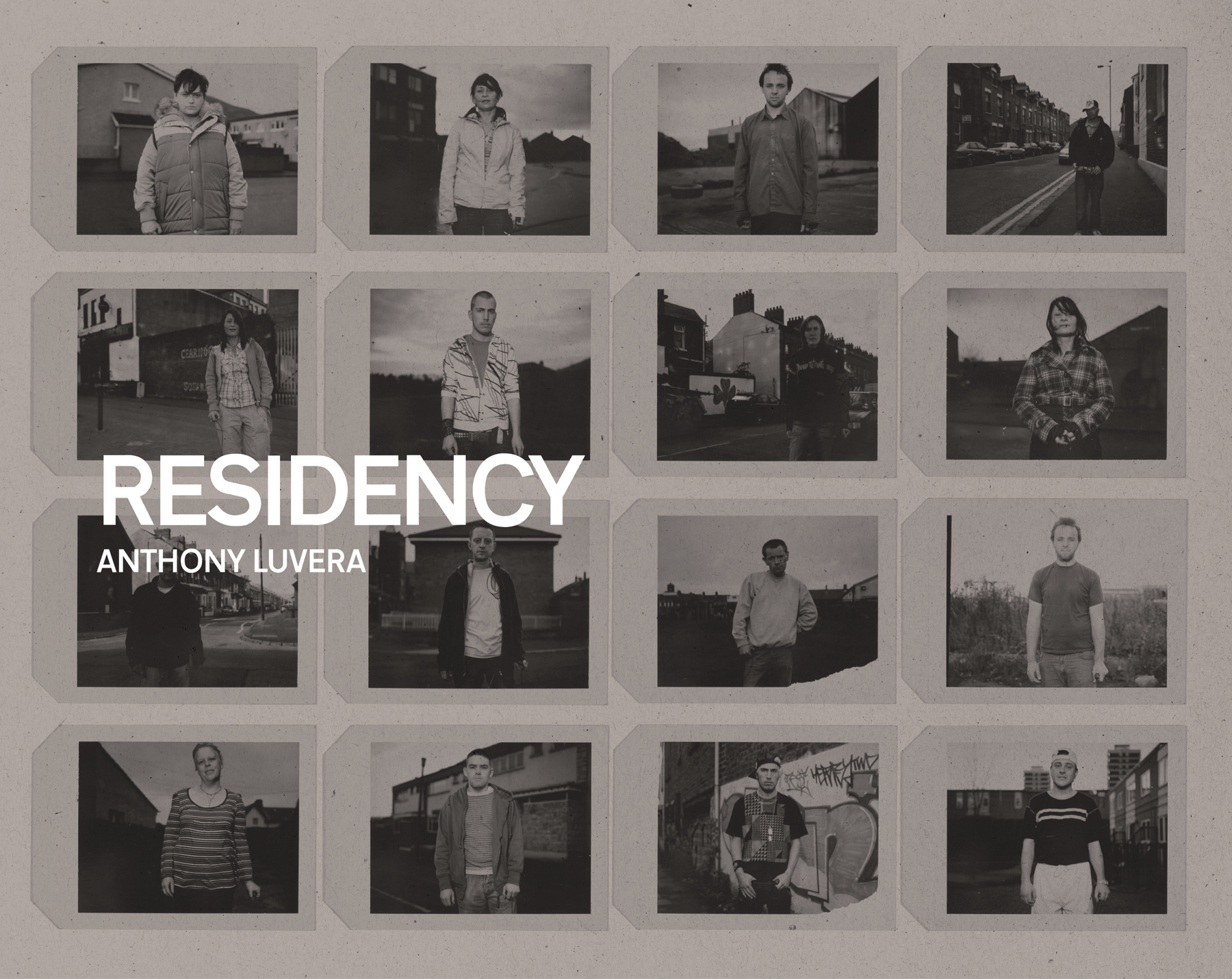

After several weeks I invited participants to learn how to use large-format camera equipment to create an Assisted Self-Portrait. I met with each participant several times to teach them how to use a 5×4 field camera with a tripod, handheld flashgun, Polaroid and Quickload film stock, and a cable shutter release. The final image was then edited together. My aim was to enable the participant to play an active role in the creation of their portrait. Each Assisted Self-Portrait is the trace of a process that attempted to blur distinctions between the participant as a ‘subject’ and myself as the ‘photographer’ during the photographic sitting.

When creating an Assisted Self-Portrait I asked each participant to take me to a place they found interesting, memorable or significant in some way. I was guided on many personal tours across Belfast. The urban landscape of the city seemed to be changing fast and I found this transformation fascinating. A loud process of (re)construction was taking place as fortifications and derelict buildings were being dismantled to be transformed by the glass and steel confection of contemporary architects. The high streets appeared to be lurching up to speed with the rest of the UK. Yet just as interesting to me were the quieter streets, closes and alleyways of residential housing estates and neighborhoods with distinctive names like Shankill, Clonnard, Whiterock, Springmartin or Holylands. The identity of each community seemed to demarcate itself from the next with displays of bunting, flags, painted curbs and murals, or in a more subtle red brick, privet-hedge and venetian blind kind of way.

Accompanying participants to visit sites where their past experiences had played out or to the places where their hopes were located seemed to add an important dimension to the process of making the Assisted Self-Portraits. For Angela Wildman it was the nostalgic pull of an address that was once a family home that she had not revisited for over a decade. Chris McCabe took me to the grounds of the children’s home where he spent much of his youth. To make his Assisted Self-Portrait Sean McAuley set up the camera equipment next to a peace line in an area he had lived his whole life before experiencing issues with accommodation. Sean told me that he saw this part of Belfast as being particularly significant to him for it had been razed and rebuilt after a Troubles-related arson attack. He said that he hoped to reestablish himself there again soon. Through these and the many other journeys I took with each participant I came to develop my understanding of the particularity of the topography of Belfast, and the outlook and experiences of each individual. In light of this I felt it important to document the process of working with each participant in the various sites that held meaningful associations for them, in an attempt to emphasize what I saw as a reclamation of place by the individual.

Towards the end of the time I spent working on Residency I recorded sound interviews to ask participants about their experiences of being photographed or filmed before we met, their thoughts on representation more broadly, and their impressions of the experience of contributing to my work.

“A wee while ago I couldn’t have imagined myself ever being homeless. And it’s what I am but it’s just another thing and I’ll move on to something else. Hopefully. But I’m very positive about the whole thing you know. Homelessness isn’t always a bad thing. It’s something that’s an experience and then hopefully you get yourself together and then you move on. Lots of people have referred to me as vulnerable. I hate that bloody word because I’m bloody well not. I don’t see myself that way at all. I’ve been through a lot and okay silly and daft things have happened, but I’ve come through and I’m stronger.”

Angela Wildman

“The first time I was a bit apprehensive about it. Thinking like I haven’t took photos of myself before. I don’t really like getting photographed. But then having to do it myself, to me, was … I don’t know. I was just thinking what am I taking a photograph of me for? It’s a bit big headed but I enjoyed it. After the first time it was pretty good. It started getting easier. I felt part of it, so I did. At the start I did really think, this isn’t for me, it’s a bit boring. But the second time I really enjoyed it, like setting up the camera and stuff, it was brilliant. But my first initial reaction was like, what is the point like? Who wants to know anyway? It’s just these homeless persons. So?… I actually thought it came out pretty good in the end. Aye I thought it was more than okay.”

Sean McAuley

Many of the stories, opinions, ideas and experiences I heard about reminded me of Stuart Hall’s writing on representation and how identity might be most usefully understood “as a ‘production’ which is never complete, always in process and always constituted within, not outside, representation”. Much of the work I undertake with people who have experienced being homeless is based on inviting the ‘subject’ to take part in creating a self-representation. It seems to me that forms of self-representation may go some way to broadening an understanding of individuals who are generally depicted through their experiences with charities, law and state services. Birth and death certificates, education reports, electoral roll details, housing status, health records, legal documentation and other official registrations or descriptions can only provide a limited outline of the life experience of any person. Filling in some of the remaining gaps and absences with the first-hand representation of the points of view of people who would otherwise leave little material trace of their lives may offer a more complex, nuanced and varied understanding of the experience of being homeless. However, while handing over the camera to a subject / participant may offer the individual an opportunity to express their point of view it won’t necessarily get the artist or audience any closer to ‘reality’. Self-representations will always be framed, directly or indirectly, by the artist or organization facilitating the process. Issues of control, context, reception, authorship, ownership and agency are always in play in any participatory practice.

The images in this book attempt to represent some of the engagement between the participants, the medium of photography and me. I am committed to continuing to work with the growing collection of photographs made in London, and now those made in Belfast. It is an ongoing process propelled by the relationships the participants and I have built, my inquisitiveness about how they understand and wish to represent their experiences, and my interest in exploring the potential of presenting their point of view alongside my own.

Anthony Luvera