Published in Footnotes

Edited by Sarah Pierce and Julie Bacon

University of Ulster, 2007

‘Dear Karen,

One of the things that strikes me most about the conference is the idea of archives as agencies for histories and representations of the otherwise unseen. Particularly Judit Bodor on Artpool for avant-garde art practices and Pat Cooke speaking about the prisoners of Kilmainham Gaol and the invisibility of the underclass […]

Anthony’ (1)

By chance, our early discussions about the possibilities and issues involved in constructing a public archive coincided with a symposium organised by Interface called ‘Investigating Archives’ as part of ‘I Confess That I Was There’. We were present as a diverse range of approaches to interpreting, managing and subverting archives were explored. Later we were invited to contribute footnotes to a review of ‘I Confess…’ and this invitation has prompted us to draw upon things that were said in consideration of our own forthcoming research project. We would like to acknowledge this request, this ‘external provocation’ (2) as an opportunity to explore and experience a small part of the Interface archive and to intensify our engagement with the ideas and problems of archiving. Our research, to be conducted over the course of a year, will be based on questions arising from an ‘active archive’ (3) Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits, a 6year working engagement between an artist (Anthony Luvera) and homeless and ex-homeless people living in London. In the process of this working engagement, thousands of photographs have been produced by hundreds of people. Photographs continue to be produced and archived. The question of whether, and if so how to present this archive in a public form, with its inherent ethical, aesthetic, technical and political implications will form the basis of our research.

‘How do I house a homeless archive? Archives are not impartial. Nor are they mute. The stories they tell are generative of histories. Real and straightforward, fictitious and scrambled. History is the stuff of oppositions, and archives in themselves are oppositional apparatuses. The archive is always defined by its relation to what it does not contain.’ (4)

Over the next few pages we will discuss the nature of the project through which the photographs were produced and some problems (with representation) that the project was conceived to investigate. In mind of the ideas and experiences discussed while ‘Investigating Archives’, we will set down some thoughts and questions that will inform our research into the potential public presentation of this archive.

Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits: Producing a photo archive

‘How do we represent the presence of the poor in history? The fact that they existed at all…’ (5)

‘collaboration

1. united labour

2. traitorous cooperation with the enemy’ (6)

In 2001 I was invited to photograph at a large shelter event for homeless people in London. I declined, smarting something about preferring to see what the people I met would photograph. Contributing to a “find-a-bum school of photography” (7) holds no interest for me. However the invitation stimulated my interest in representations of poverty and homelessness, and in questions about the process of representation itself.

Photography has always been implicated in problematic representations of the poor. The earliest deployment of the medium as ‘documentary evidence’ in support of social reform campaigns at the end of the 19th century, by the likes of Thomas Anan, Jacob Riis and John Thomson (8) established the tropes of a social documentary use of the photographic medium. An aesthetic and its production methodology was settled, and proceeded largely unquestioned. That is, until the appropriation of the photographic text in conceptual art practices of the late 1960s and 1970s (9), and the evolution of critical theoretical discourses on photography, propelled largely by the work of the German Marxist philosopher Walter Benjamin (10). All of which has significantly contributed to the revelation of a ‘documentary photography’ in absolute as a sham. The traditional formulations of the truth-telling genre have been exposed as a composite of stylistic conventions and production methodologies applied to spectacles of abjection, preferencing a celebration of photographer’s ‘genius’ over and above an effective consideration of the documentary concern. However, we still continue to persist with the production and consumption of photographic representations of social difference.

More recently artists and writers on photography such as Martha Rosler, AD Coleman and Alan Sekula (11) to name a few, have urged practitioners to further develop the methodologies utilised to create and disseminate the documentary photography project: to re-think the possibilities for the roles of the photographer, the subject, and the medium itself. To conceptualise strategies that include the subjectivity of the subject, alongside that of the photographer in the final presentation. Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits was initiated as an investigation into re-thinking the possibilities for the ‘negotiation’, or collaboration, between myself as the photographer, the subjects as participants and the actual use of the medium itself.

I went along to the event and helped to serve food, organize karaoke and give out clothing, toiletries and blankets. When it was appropriate I spoke to the people I met about an idea I had for a photography project. I explained that I wanted to collate an archive of images made by homeless and ex-homeless people, and that anyone interested could come and see me in various places across London, to collect cameras and photograph whatever they liked.

Over the following six years, and still continuing today, over 250 people have attended weekly drop in sessions to contribute to the archive. The sessions are always high-energy, swarming with vibrant personalities. The youngest participant is 19, the oldest nearing 90. People get involved for different reasons and have different ideas about what they want to photograph. I explain how to use the cameras and listen to each participant’s ambitions, encouraging everyone to simply go and do it. I never bring along photography books or show my own photographs, nor do I tell any of the participants how or what to photograph. I ask each participant to pull out their favourites, or the images that best represent what they want to show. With permission I take scans of the images and store the digital files and negatives. Release forms and licenses are provided, written especially for the project by specialist intellectual property copyright lawyers. Permission is not always given, and this is respected.

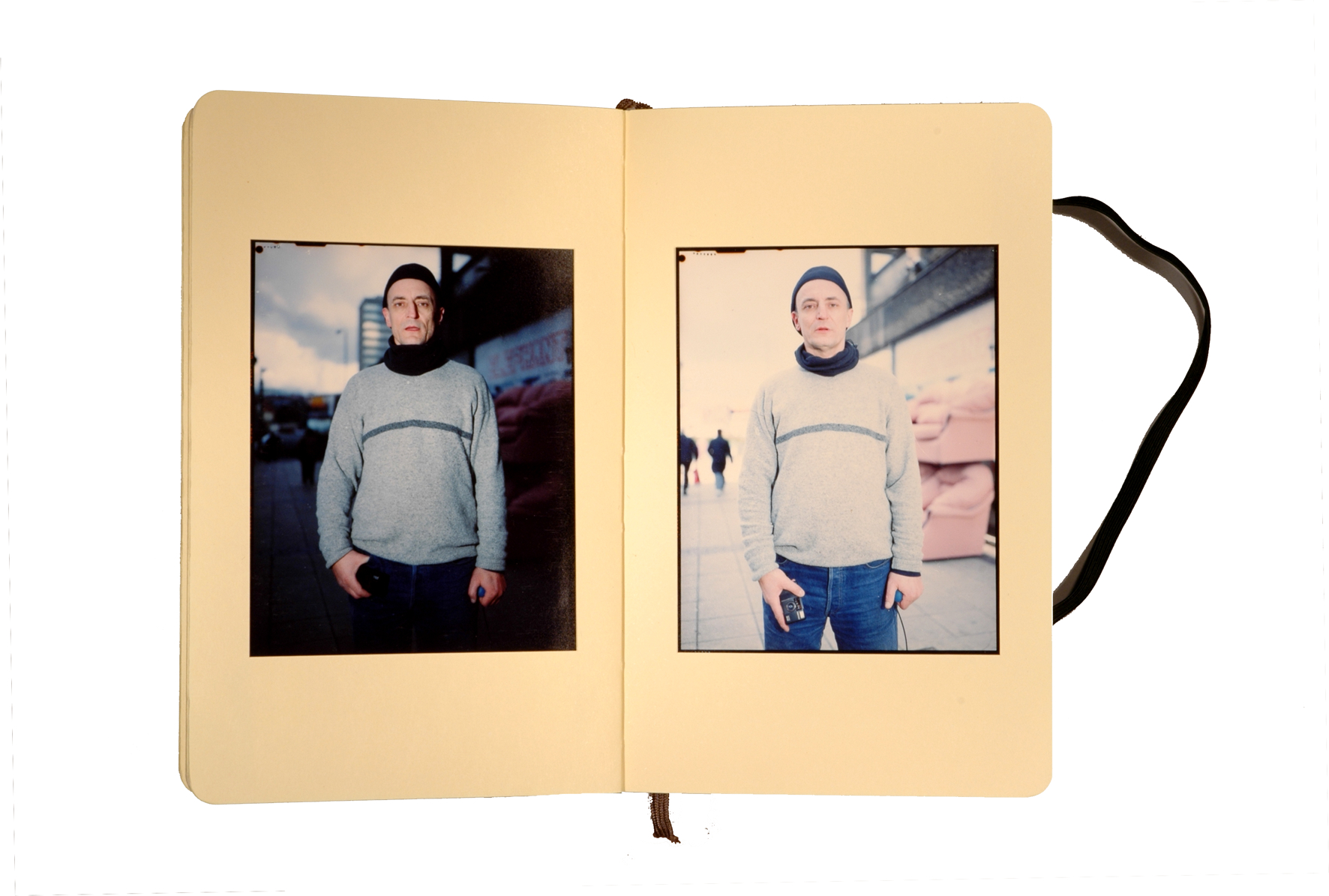

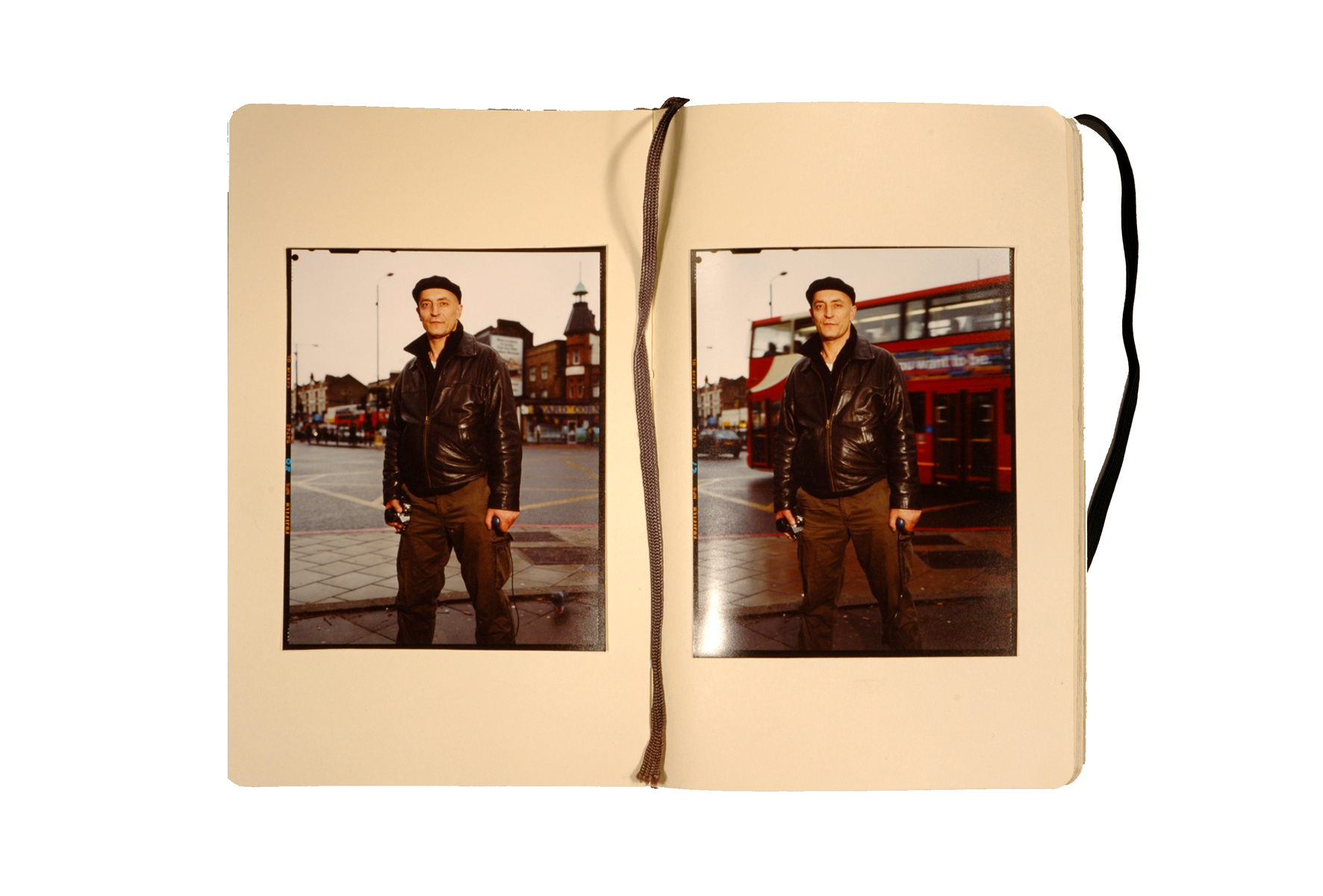

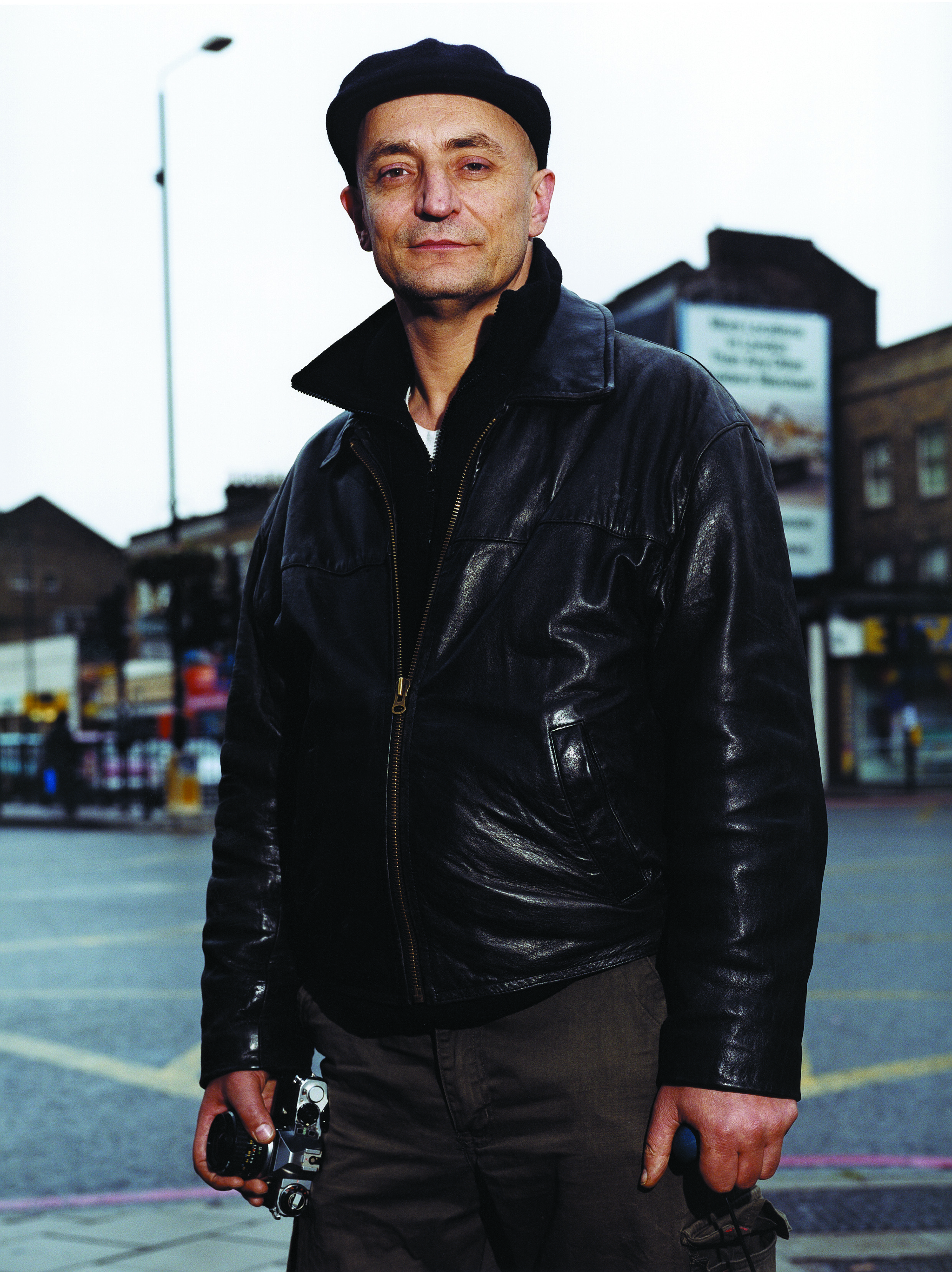

The prospect of an opportunity to publicly exhibit photographs from the archive on the London Underground’s Platform for Art project in 2005, necessitated that I give careful consideration about the importance of recognizing the individual creators of the images. I did not want to simply put out an unconnected presentation of images attributed to ‘homelessness’. I began to think about how to create representations of the contributors to the archive, in a way that would react against the process of a traditional portrait making exercise.

In order to research and determine the production methodology for an Assisted Self-Portrait, I worked with one participant, Phil Robinson, for over a year. To experiment with technical setups, and to closely examine the negotiations played out during in the photographic transaction. We tested ways to use various camera formats, with different lighting systems, film types and ways to physically trigger the exposure of the image. Arriving at a technical arrangement consisting of a large format camera, tripod, handheld flashgun, Polaroid and QuickLoad film stock and a long cable release. These preliminary technical experimentations were crucial in workshopping the instructional aspect of the portrait making to enable the participant to take control of the process, calling upon me as an assistant to their image making. Technical knowledge is built up through a number of meetings over 6 to 8 weeks. The final image is edited with the participant and the use of the Assisted Self-Portrait is always with their consent.

Each Assisted Self-Portrait is the trace of a process that aims to blur distinctions between the subject, and myself as the ‘photographer’, during the photographic sitting. Investing in the participant a more active role in the creation of their portrait representation than is usually offered in a traditional photographer-subject relationship. In doing so the participant/subject become a co-creator of the image, and I, as the photographer, act as a facilitator and technical advisor.

Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits, and other photographic and video works that have developed out of the initial archive project are investigations that seek to rethink production methodologies and strategies for representation. To actively depart from a fixed point-and-shoot habit in the conception, creation and presentation of a ‘documentary’ project, to find ways that might usefully unshackle the roles of each within this triad.

Thoughts on Photography and the Archive: Informing research

Having been there, it was interesting, and strange to experience ‘Investigating Archives’ as an archival object, to look through six, hour-long DVD recordings supplied by Interface. It was a very different order of experience. One’s role changes from observing and participating in the event, to a solitary exploration and slow, forensic analysis of what was said and how it was shared. One is also in a position to direct the order and pace of things. The volume can be raised if you can’t hear what’s being said and the speaker can be stopped and made to repeat themselves if you missed it the first time. The camera lens brings the speaker very close and the high definition recording technology renders the speaker; their manner, their performance in richly textured, luminous detail. It’s a powerful experience. It’s also a responsibility. We have a responsibility to refer to it, and to use it; interpret it and make it meaningful. In reviewing the symposium, it is no longer sufficient to refer to our scribbled notes. We are obliged to comb through the archive, to draw upon the document as opposed to our memory. The document becomes the authority and our memories subservient to it. After one of the presentations, somebody from the floor suggested that ‘archiving can be seen as the regulation of knowledge, the disciplining of experience, the reduction of relationships to resources and the protection of resources’. This is an issue, regardless of how ‘objective’ and sophisticated the documentation, it is always just an interpretation, partial and limited. However, typically the fact of the fallible and protean nature of the archive is absorbed in the fiction of the archive as a key to truth. John Gray remarked with irony on the ‘librarian’s logic’, ‘the notion that the route to ultimate knowledge is to catalogue everything’ (12). Walid Raad admitted a loss of faith in the reductive nature of this logic, indexing exhaustively and yet always aware of slippage, of an absence, something not recorded. In describing the inadequacy of the archive to represent experience he refers to how a history of the destruction of the twin towers wouldn’t be complete without a record of every shade of blue in the sky. Similarly he speaks of how a true record, a complete ‘history’ of the glass of water in front of him would not only have to be recorded from every perspective, but would also have to be recorded through every second in time:

‘What is there to guarantee that the cup full of water at 3.17 is the same cup at 3.18? Now let’s imagine a system of archiving that tries to keep up with that.’ (13)

The archive is always partial; it is always an interpretation based on a decision to include one thing and exclude another. It is an oppositional apparatus. Photography is similar; it is structured on exclusion and absence. It is always subjective, always a record of a selected part of something. Not only is photography subjective and partial but also, it’s meaning is contingent. It’s meaning, or the readings that are made of it are for the most part determined by the context in which it is presented (14). Photographs are generally created within institutionalized systems of production (police photography, family photography, medical photography etc.) and are understood through conventionalized systems of reading:

‘What lies ‘behind’ the image is not reality – the referent – but reference: a subtle web of discourse […] a complex fabric of notions, representations, images, attitudes, gestures and modes of action which function as everyday know-how, ‘practical ideology’, norms within and through which people live their relation to the world.’ (15)

Photographs are understood to stand for ‘what was there’, what happened. Many critics have written about the problem of the invisibility of photography’s mode of production, the lack of acknowledgement of photography as a medium, as a process through which meaning is constructed. Pat Cooke comments on the role of archives as mediators between the real and imagined. He refers to objects in collections as semaphores, as ‘objects removed from everyday use and given a special role as mediator between visible and invisible worlds’ (16). This symbolic function, the capacity to represent and to produce the conditions in which we can think about and imagine the past, is part of the power and attraction of archives. But the business of representation is difficult and responsibility for an archive is fraught with risk and compromise. Its assembly always prioritizes certain readings and creates specific histories. These histories are always incomplete and inadequate but they are also important.

The beginnings of a research project; some questions

Consideration of the complexities around the public presentation and use of material from Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits has become imperative, as increasingly organizations and persons outside of the project show interest in the presentation and use of the images (17). The research residency facilitated by Belfast Exposed is designed to support the exploration of various practical and theoretical considerations for manifesting Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits as a public archive.

The research will draw upon the Belfast Exposed archive project as a key case study, along with other local and international resources, and artist practices. It will reflect on the residual status of the material in the archive, existing beyond the processes of its creation, and independent of a relationship with the artist. The implications of enabling the archive to function as a resource to be accessed, explored and used will be considered. How should it be accessed? By whom should it be accessed? What caveats could or should be placed on outsider use of the images?

The research will aim to assess the implications of organizing the material into a classificatory system, supplementary to what is already inscribed through the rudimentary practice of assembling it over the past six years. It will examine the implications of the material being contextualized outside of the considerations in which it was created, particularly within mainstream discourses or representations of homelessness.

Should the photographs be seen only within the context of the practice of the artist, or whatever uses the contributors have for the images?

Is the archive a resource, or a composition of the artist, or a manifestation located somewhere between the two?

How will all of this impact on the agency of the archive in the production and dissemination of non-mainstream histories?

Footnotes

(1) Extract from an email sent by Anthony Luvera to Karen Downey on 6 June 2007

(2) When asked by an interviewer where he got his idea for a book or article Derrida replied:

‘A sort of animal movement seeks to appropriate what always comes, always from an external provocation. By responding to some request, invitation or commission, an invention must nevertheless seek itself out, an invention that defies both a given programme, a system of expectations, and finally surprises me myself – surprises me by suddenly becoming for me imperious, imperative, inflexible even, like a very tough law.’

Derrida, J. (1995) Points … Interviews, 1974-1994, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, p352.

(3) Judit Bodor describes an ‘active archive [as] a specifically artistic activity [which] not only collects and archives that which already exists but instead through its projects generates further material susceptible to archival processes.’

Bodor, J. (Nov. 2006) ‘Artpool:the ‘active archive’ of Hungary’. Investigating Archives. Symposium conducted by Interface at the Linen Hall Library, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

(4) Extract from an email sent by Anthony Luvera to Karen Downey on 6 June 2007

(5) Cooke, P. (Nov. 2006) ‘Perish the Thought: addressing absences in collections through exhibition and performance’. Investigating Archives. Symposium conducted by Interface at the Linen Hall Library, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

(6) The Oxford Dictionary of English, 2005, Oxford University Press, Oxford

(7) This is a reference to Martha Rosler’s seminal critique of documentary photography:

Rosler, M. (1981) ‘In, Around and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography)’ in Rosler 3 Works, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Press, Halifax.

(8) Thomas Annan was commissioned in 1868 by the City of Glasgow Improvement Trust to document the alleys and closes of the slums of Glasgow to create a case for their demolition. John Thomson published images of Street Life in London in 1878. Jacob Riis was a journalist and social reformer who published How The Other Half Lives in 1889, and is also credited as being one of the earliest users of flash-powder photography, which he used when photographing in the flophouses of New York City’s Lower East Side in the middle of the night, rendering the half asleep subjects in a bleary eyed stupor.

(9) Particularly those centred on self-reflexive investigations of the medium (such as John Hilliard, Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, and Douglas Heubler) and those informed by interdisciplinary elaboration and critique of the human sciences, especially within discourses around ‘otherness’ in psychoanalysis and anthropology (such as Martha Rosler, Susan Hiller, Louise Lawler and Mary Kelly).

(10) Especially Benjamin’s seminal essay ‘The Author as Producer’ originally delivered as a lecture in 1934 at the Institute for the Study of Fascism in Paris [Benjamin, W. (reprinted 1982) ‘The Author as Producer’ in V. Burgin (ed) Thinking Photography, Macmillan Press, London.]. And later the through the evolution of discourses significantly impelled by the work of writers such as Susan Sontag [Sontag, S. (1978) On Photography, Penguin, London.], John Berger [Berger, J. & Mohr, M. (1982) Another Way of Telling, Writers and Readers Publishing, London.], Martha Rosler [Rosler, M. (1981) ‘In, Around and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography)’ in Rosler 3 Works, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Press, Halifax.], and Abigail Solomon-Godeau [Solomon-Godeau, A. (1984), ‘Inside/Out’ in Public Information: Desire, Disaster, Document, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.].

(11) Alan Sekula: “A truly critical social documentary will frame the crime, the trial and the system of justice and its official myths. Artists working toward this end may or may not produce images that are theatrical or overtly contrived, they may or may not present texts that read like fiction. Social truth is something other than a matter of convincing style.”

Sekula, A. (1984) ‘Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Photography (Notes on the Politics of Representation)’ in Photography Against the Grain, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Press, Halifax.

(12) Gray, J. (Nov. 2006) Plenary Session, Investigating Archives. Symposium conducted by Interface at the Linen Hall Library, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

(13) Raad, W. (Nov. 2006) Plenary Session, Investigating Archives. Symposium conducted by Interface at the Linen Hall Library, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

(14) David Campany talks about how ‘photographs are signs (in the semiotic sense) … [and] their relation to any particular site will only ever be provisional’. He goes on to say that ‘the condition of being a sign is that it always carries with it the potential of ‘contexts to come’’.

Campany, D. (2003) ‘ “Colourless green ideas sleep furiously” Photography and the syntax of the archive.’ in Source Vol 36. Autumn 2003. pp14-17

(15) Tagg, J. (1987) The Burden of Representation, Macmillan, London, p. 102

(16) Cooke, P. (Nov. 2006) ‘Perish the Thought: addressing absences in collections through exhibition and performance’. Investigating Archives. Symposium conducted by Interface at the Linen Hall Library, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

(17) Most recently, in May 2007, a selection of images from Photographs and Assisted Self-Portraits, was featured in “1+1=3, Collaboration in Recent British Portraiture” at the Australian Centre for Photography, curated by Susan Bright. Various organizations, including bible manufacturing companies and social work agencies, have requested to use images from the archive for commercial purposes or in contexts outside of my practice as an artist. These kind of requests have been declined or deferred until concrete decisions about the manifestation of the archive have been made.