Published in Cities Methodologies Bucharest, 2010

Edited by Ger Duijzings, Simona Dumitriu and Aurora Kiraly

Anthony Luvera (AL): What a great recording device you’ve got here.

Margareta Kern (MK): It’s really handy. I use it a lot in my work when I interview people.

AL: Do you have a collection of sound recordings that accompany Guests, the work presented at Cities Methodologies Bucharest?

MK: Yes. Although when I made the recordings my inclination was to use transcriptions and this is what I told the women I interviewed. In the beginning of my work on the project I was focused on researching and hearing about their personal experiences of migration as I found that these stories were largely missing from official histories and national archives. I was looking at ways to record their stories and at the same time be sensitive to their privacy.

AL: Do you feel that the translation that occurs when you transcribe an interview offers some kind of protection for your subjects and you?

MK: I feel it can provide protection to the subjects by offering anonymity. They can speak more openly and freely about their personal experience but it can also make them invisible. For me it provided a certain degree of freedom to be able to edit the text without being tied down by the original document.

AL: I can relate to some of what you are saying here. When conducting interviews with participants for Residency I explained that I might use the sound recording or a transcription with their Assisted Self-Portrait and photographs. I wanted to be as clear as I could about my intentions for the recordings but at the time I didn’t know exactly how I would use the interviews or if I even would. It was very much a process of research and exchange based on trust and my curiosity about their lives. I was keen to hear about the participant’s earliest experiences of photography and to learn about how they felt about being described or represented as homeless.

I’m interested in how the processes of transcription, editing, quotation or selection might alter the original documents, the original terms of the invitation issued to the participant, or the interviewee’s intentions for agreeing to take part in the work. In much the same way that we’re undertaking this process of sitting here, drinking coffee and recording our conversation, when it comes to editing and transcribing the recording it will be transformed and be manufactured into something else.

MK: I think a degree of editing in any representational process is inevitable and necessary if we are to create the work we feel satisfied with. But the editing process happens before transcription. When you and I switched the voice recorder on just a few moments ago something shifted. We know we are being recorded and in a way we become more aware of editing ourselves before we speak. When I stepped into the living rooms of the migrant women there was a shift because they didn’t know me. They would have only just met me and were probably thinking: “who are you? what do you want?”

AL: Did you find that moment uncomfortable?

MK: Yes, absolutely.

AL: I love how in that kind of moment the recording device, whether it’s a camera or a piece of sound recording equipment is very much, as Susan Sontag described, a kind of a passport. For me it’s a moment full of discomfort and curiosity. I have ambivalent feelings about this experience but I find it compelling at the same time.

MK: This discomfort doesn’t have to be negative thing. Perhaps it’s also about being in a new space, an unknown space, where you’re not feeling sure of what is going to happen. Recently, I undertook a residency in the department of Social Science at the University of Bath where I was talking to a sociologist about the double-bind of being an insider and an outsider that researchers often face, and how this creates a level of discomfort. He said that he saw this as a constructive discomfort – much along the lines of how you described it. In the context of art making I see it as a form of critical discomfort. It sometimes feels exciting and sometimes it’s terrifying.

AL: One of the things I’m keen to do with the people I work with is to address something of the source of this discomfort by asking questions like; ‘what do you think about being represented or described in a certain kind of way?’ or ‘how would you like to be represented?’ To make an Assisted Self-Portrait I met with each participant a number of times in various locations chosen by them to teach the individual how to use a 5×4 field camera with a tripod, handheld flashgun, Polaroid and Quickload film stock, and a cable shutter release. The final Assisted Self-Portrait was then edited with the participant.

I’ve always been interested in seeing how I might involve subjects or participants in the process of creating their representation. More recently I’ve wanted to explore how I might extend this conversation in relation to exhibiting the work and in possibly constituting the collection as a public archive. A short time ago I was invited to take part in a festival in London called This Is Not A Gateway. I decided to focus on three participants called Ruben, Picwick and Gypsy, and to invite Ruben to work with me to install the work in the exhibition.

MK: How did it go? What was the exchange between you like? What was Ruben’s response?

AL: I brought a stack of material to the exhibition space; photographs, workbooks, Polaroids, drawings and Assisted Self-Portraits. We tested out different selections and arrangements of the material, and ways of putting the work up. It was very much a process of us both trying things out and discussing what we liked and what didn’t like, and why. It was a process of push and pull from both sides; a negotiation focused on constructing a story using the material that I have collected. In the end Ruben said he was happy with how he was represented and he came along to the private view with a number of his friends and seemed to take great pleasure in the night.

-

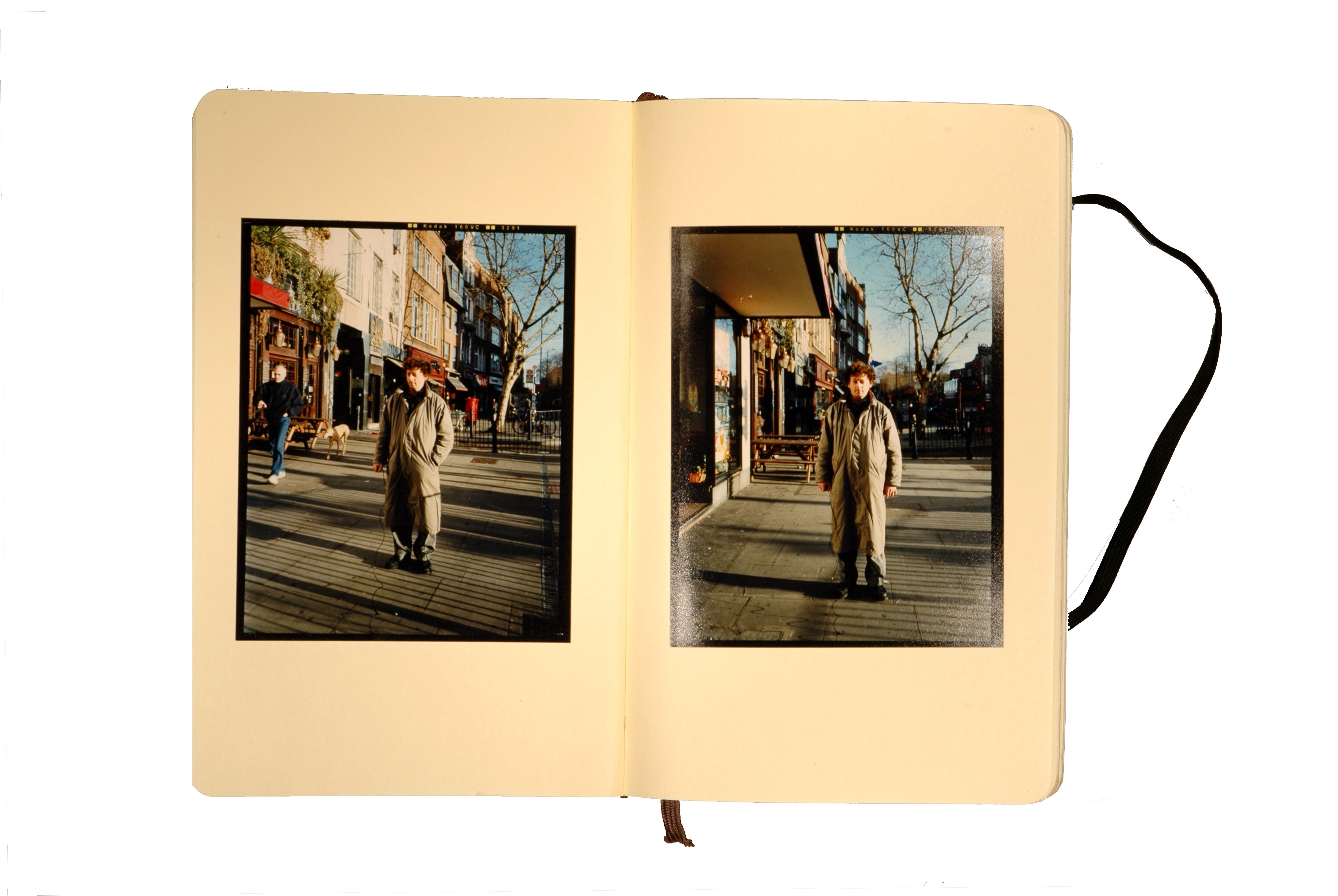

Workbook for Assisted Self-Portraits, featuring works in progress with and of Ruben Torosyan, Ruben Torosyan / Anthony Luvera

MK: I find your series Assisted Self-Portraits very interesting in that respect. You seem to be addressing questions of self-other representation through the title and also through the image where we can see the subject operating the cable release with their own hands. To me this seems a key component to the work – the fact that the camera is triggered by the person in the photograph. We as viewers are made aware that we’re looking at portraits of people who have experienced homelessness – an experience I associate with a lot of uncertainty and vulnerability – and seeing them using the cable release becomes an incredibly potent symbol of their own agency over their lives and over the production of the image.

When I started working on Guests I became fascinated with how academic researchers working in the social sciences negotiate the process of research with tangible outcomes and the level of fictionality that this process brings with it. I think every text is very much constructed. I think everything is constructed.

AL: Certainly. Even when research projects or processes are purportedly conducted in a way that is seen as organic, first-hand or transparent, there will always be a level of interference, manipulation or construction involved in someway. Prologue to Isha was the first time I picked up a video camera with an intention making something for public display. I wanted to record everything in my encounter with Isha with this equipment – the process of preparing for the interview as well as the actual interview – so I switched the camera on pretty much as soon as I stepped through the door. Then in editing the footage what seemed to most effectively represent my interests in documentary representation was this setting up process; tthe push and pull of the relationship between myself as the photographer or artist, Isha as the subject and the recording equipment as a conduit. It seemed right to dispense with the documentary interview itself and just retain the prologue to the interview.

MK: So in a way you turned the camera on to the mechanism of construction rather than the constructed story.

AL: Yes, although even this may be seen as the creation of another story. Something that was edited, selected and narrated in various ways. This has been one of the threads I’ve been keen to explore in much of my work. One of the key components of Residency are images that document some of the process of working with participants. Selecting these images was uncomfortable in some ways. For even though they might be seen as providing a view into the process of constructing the Assisted Self-Portraits, a certain process of editing and selection also occurred in order to incorporate these images.

MK: It seems to me that you are alluding to layers of construction that presuppose there is an authentic moment when the layers are peeled off and that all other moments are just constructions, whereas I am not so sure. On the other hand I am really wary of going to the other extreme, and saying there is nothing there when we peel the layers of construction. I think there is a tension between different modes of construction, or different realities, and their representation. What both our practices are trying to engage in, I believe, are social realities of others, our own and the critical issues around the representation of this engagement.

AL: I agree that the idea of a pure or authentic representation of reality is flawed, but what I am more interested in is seeking out possibilities for sharing the subjectivity presented in the work that I make. To find ways to learn about other people’s experiences and points of view, and to devise ways to represent these alongside my own view.

MK: But do you think you can ever represent those experiences?

AL: Well I do think it’s possible to represent the people I work with and something of their experience of the world but I don’t think these representations, whether they are created by the participant or me, are necessarily the truth.

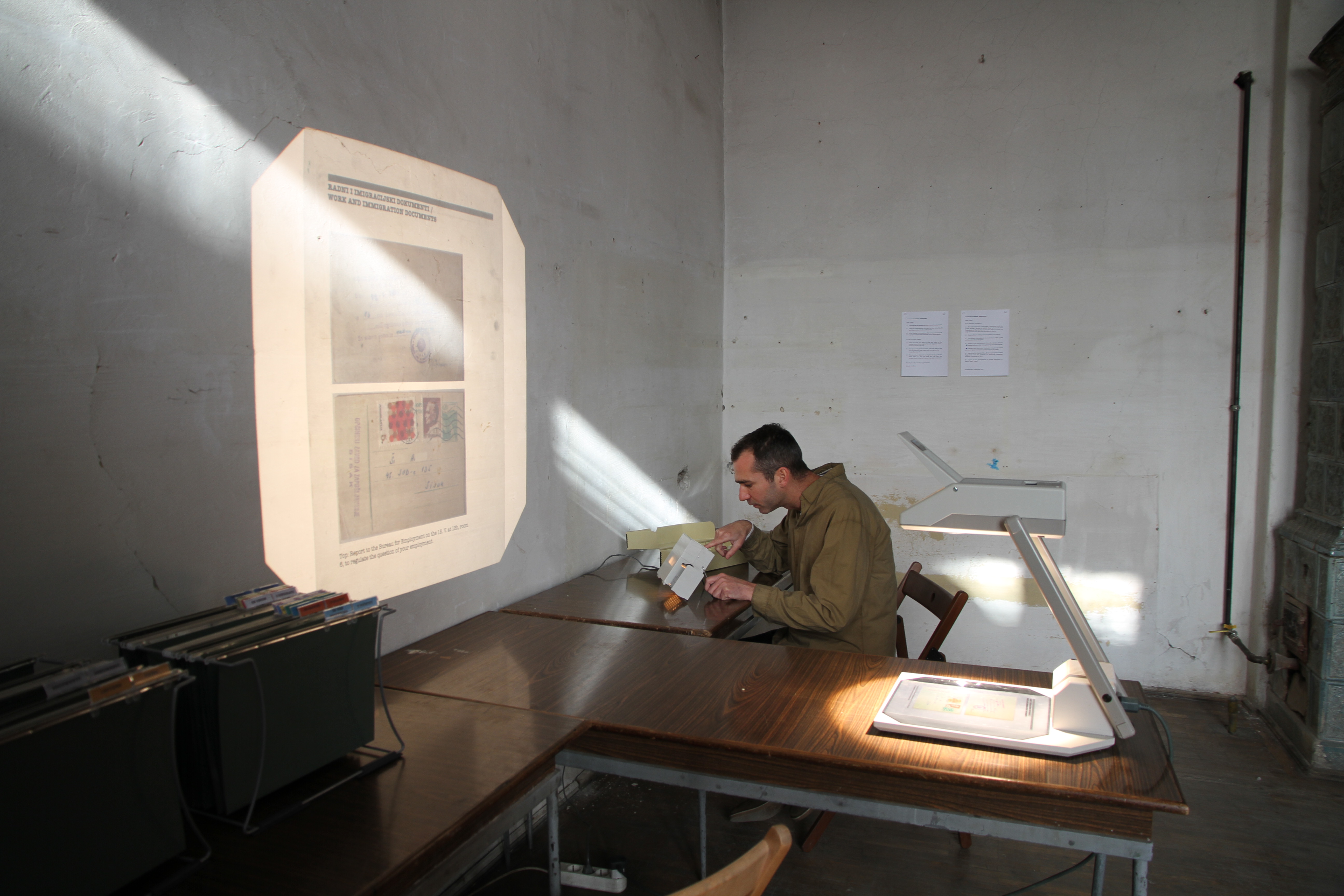

One of the things I find interesting in your work is theis idea of manufacture or a manufacturing of other people’s memories or experiences through participation. How you create a kind of workstation in which the audience is invited to activate. I like how there is not just one line of narrative that the viewer is invited or prompted to follow but rather how there are a number of different storylines to pursue and assemble. The audience is very much invited to actively construct his or her own route through the material. I’ve found it interesting to watch you develop this body of work over the course of a number of years, unfolding different presentation strategies for the same collection of visual and written material.

MK: Yes, you saw this work develop right from its first showing in CitiesMethodologies London in May 2009. Over the past year and a half I have used different strategies of display in order to work through the research process and to understand different types of materials, and vantage points I can take. I’m glad to hear from you that a sense of manufacturing or constructing multiple narratives comes across as I felt this was important to attempt to convey. In the end I wanted to bring into the piece that experience of working through the material and to give the viewer an active position of a creator of meanings and narratives. I wanted to make theat process of creating stories by the viewer more conscious, which is why the work is set up as a cross between a research space, an archive and a workstation.

AL: It seems to me that we both share a strong interest in the research methodologies of the social sciences. I have always been very curious about the relationship photography has to these processes and strategies for acquiring and representing knowledge. Especially in relation to how photographs might be used in archives. In a sense it is in archives that photographs are able to function in their most pure state as free-floating bundles of information poised to be anchored by context. The slip and slide of different contexts by different archive-users may have for the same image is potent.

MK: It’s what makes photographs so wonderful. So interesting to work with.

AL: Especially in relation to how an individual might be represented or perceived. How have the women themselves engaged in the process of manufacture in the installation of Guests?

MK: One of the women I met in Berlin, Zora, came to a collective reading of the transcripts during a group exhibition called ‘Exposures’ that recently took place at an ex-factory in Banja Luka, Bosnia-Herzegovina. There was an interesting moment when after different people in the audience took turn to read out sections from interviews, Zora was asked why she decided to leave Yugoslavia in the late 1960’s. She spoke about her experience of moving as a ‘guest worker’ to Berlin and her reasons for staying on to live there for nearly forty years. There was something really moving about that moment, something so direct and spontaneous.

Currently I’m thinking about ways in which I want to engage the women further with the project, especially in the light of Zora’s spontaneous contribution to that public event. I have remained in contact with all of the women I interviewed, and I’ll be returning to Berlin in a couple of months to visit them again. I’m considering whether to keep my engagement with them private or to make it more public, or whether I should incorporate them in the work more directly.

AL: Do you need to? Why do we need to represent the experiences we undertake as artists?

MK: This is a very interesting question. Perhaps it’s partly because if we don’t have ‘proof’ the engagement took place then our interactions with others are absolved into life. I believe a lot depends on what position we take towards these types of engagements and their representation.

My project started during a two-month residency in Berlin, and I was expected to complete a piece of work in that period for an exhibition. However, the more I delved into the subject of memory, labour and migration, the more I felt I needed to take time to understand its complexities. I had only just made connections with the migrant women, and I wanted to take time getting to know them and their stories. I could have set up my medium format camera and taken photographs of the women in a (similar way to what I have done in the past, ), but I questioned what would these portraits tell us about the complex historical, social and political context of their migrations to West Berlin from socialist Yugoslavia in the late 1960’s? All this meant that my engagement with the work went beyond the scope of the residency and became a long-term project. Because I questioned these modes of representation and my position within them, it was a very uncertain process but more and more I am seeing how this uncertainty is the right place from which to make my work.

AL: In a similar way I felt very uncertain about flying in to Belfast every Monday and coming back to London every Thursday through the period of making Residency. I felt a double outsider. I wasn’t homeless and I wasn’t from Belfast. And I couldn’t help but have these thoughts in the forefront of my head every time I met with someone and asked them to share their photographs with me, to create an Assisted Self-Portrait or to take part in an audio interview. You’re right, it can be difficult to have confidence in uncertainty, in giving yourself over to process and following lines of inquiry.

MK: Yes. It’s like you’re on a really rocky boat and you don’t know where it’s going to take you.

Margareta Kern is a London based artist, originally from Bosnia-Herzegovina, whose practice explores the potential of image-making as a critical engagement with the social and political sphere. Using diverse methods and modes of visual mapping, Kern points to often overlooked yet formative aspects of everyday life, enabling new perspectives and narratives to emerge. A graduate of Goldsmiths College (BA Fine Art, 1998), and University College London (MA Visual and Material Culture/South East European Studies, 2010) her work has been shown extensively including Impressions Gallery Bradford, Tate Modern London, Museum of Contemporary Art Budapest, Institute of Contemporary Interdisciplinary Arts Bath, HDLU Gallery Zagreb, Kurt-Kurt Gallery Berlin, and Margaret Harvey Gallery University of Herefordshire.

Kern’s Guests is a long term, multi-disciplinary project, which focuses on the critical recovery of migrant workers’ histories, and the role that art can play in corrective historiographies. The project takes the history of women who came as ‘guest workers’ from the socialist Yugoslavia to West Berlin, in the late 1960’s, as a starting point in developing a series of works dealing with memory, storytelling and archive.