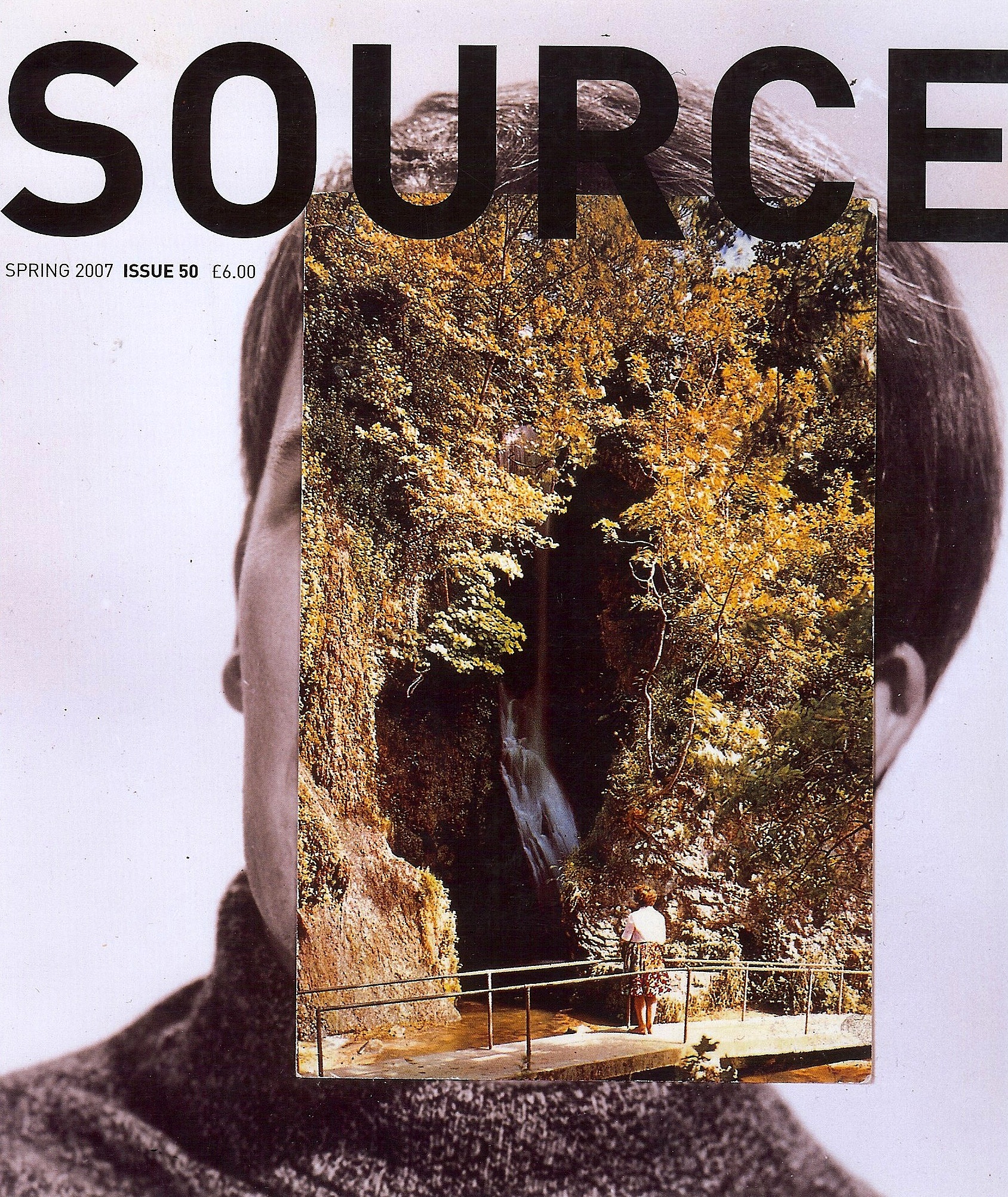

Book Review of Towards A Promised Land by Wendy Ewald (Steidl / Artangel)

Published in Source

Spring 2007 Issue 50

Reviewing a publication by an artist whose practice is driven by process, dialogue and collaboration is an intriguing exercise. It becomes more than an examination of the content of images and words spread out in a book. It throws up a different set of questions. How have they utilized the format of the book to frame their project or concern? Why disseminate the work in this way? How does the artist operate their practice and how is this revealed in the publication?

Wendy Ewald’s recent publication Towards a Promised Land charts a two-year project conducted with 20 refugee children living in Margate, a mix of British migrant children from within the UK and asylum seekers from diverse places around the world. Ewald made portraits of the children and still lives of objects that accompanied them on their journey to Margate. She then taught her subjects how to use large format positive/negative camera equipment and issued them a brief to photograph their families, living environments and dreams. Accompanying texts were also created through interviews and captions, sometimes inscribed directly on to the images. The project culminated with an exhibition at The Outfitters Gallery in Margate in July 2006 and a series of large-scale photographic banners presented on the sea wall and throughout the town. Photographs of the children’s faces looking out to sea (toward their place of origin) were juxtaposed with images of the backs of their heads (toward Margate their new home), accompanied by still lives of their personal belongings.

Ewald is an artist whose practice clearly draws sustenance from ethnographic field study models. Her collaborative way of working is facilitated through sustained projects conducted on an educational model and emulates the ‘participant observation’ visual research methods employed by the social sciences, sociology and ethnography; in particular, techniques such as ‘auto photography’ (subject takes photographs used / re-presented by ethnographer / photographer), and ‘photo elicitation’ (subject and ethnographer / photographer discuss and interpret photographs together). Using collaborative strategies of play and dialogue Ewald’s subjects are encouraged to creatively express themselves to enable her to ‘see in’ to their world to harness material for her practice. However, in doing so, it is not simply an ingenuous re-presentation of an unmediated reality that Ewald arranges, but a strategic shift of her own role as a photographer to that of a teacher, facilitator and curator. The camera is deftly re-deployed with the subject as operator, in order for Ewald to appropriate and re-frame this material within the perimeters of her own fabrication in exhibition and publication.

Towards a Promised Land presents more than a chronological account of a process-driven community arts project with documentation of resultant public artworks in situ. Ewald uses the format, layout and edit of the publication to further appeal to ethnographic associations of positivist integrity, preservation and a ‘truthful’ presentation of her subject’s ‘reality’. Ewald’s role is that of a field worker, the subjects are her ‘case studies’ and the book is the delivery of findings supported by maps and diagrams, quantitative facts and figures, extracts from the Old Testament Book of Exodus, and endorsementsfrom experts in the fields of art, photography and on the topic of Margate.

In the opening pages of Towards a Promised Land, Ewald’s area of investigation is immediately made clear through a series of quotes on migration and asylum, and an aerial view of Margate. A following double page spread filled with a grid of 20 headshots introduces the ‘case studies’. And a preface by Ewald’s commissioner, Michael Morris of Artangel, tells us that it is “their stories that we listen to”. The subjects are then presented individually through a combination of Ewald’s portraits and still lives, photographs made by the subject, and the story of their relocation pieced together from interviews, anecdotes and writings. Told in the first person narrative voice of the subject, these stories range from endearing, commonplace accounts of leaving friends, family and school in one part of the UK and ending up in another, to astounding and moving testimonies of international human trafficking and survival.

The photographs made by Ewald’s subjects are stylistically constructed within the technical parameters set out for their image making: black and white depiction, rectangular framing and harsh frontal flash. These images look like photojournalism and documentary photography and draw endorsement from these genre’s historical claims to the framing of the real. Often the representation of the abject state of those depicted is exacerbated by the disarming and potent intimacy achievable only through the proximity of the lens of a family member. However, the child-like language and first person narrative of the captions anchor the viewer’s primary attention to tangential details and quotidian actions of those depicted, inverting this association and mocking the configuration of traditional ‘slice of life’ truth-telling modes as child’s play. See the image by Elisio of a jumble of objects on utilitarian furniture in a spartan room; ‘My ad for a new kind of clock’ – Elisio, or the image by Rabbie of a glum family group crammed in an institutional dormitory stuffed with bunk bedding; ‘My family that I love’ – Rabbie.

The author Abdulrazak Gurnah gives an evocative account of 1960’s Margate and his own personal experience of discrimination as a way in to considering present day violence and racial tension, and the presence of Ewald’s banners in the town. However, Gurnah’s consideration of the repeated vandalism of the banners, which occurred after the July 2006 bombings in London, is cursory. He asks glibly, “What does it mean that all the images attacked were of girls? And what metaphors are contained in the form the vandalism took?”, and does not go on to contemplate the matter other than to declare, “it could have been worse”.

Ewald herself goes only a little further to address this issue in her conversation with Michael Morris in the book, which otherwise goes in to great, transparent detail about the production of the project. She simply describes how the subjects personally responded well to the attacks on the banners. However at a recent public conference in Newport, Ewald explained that at the time of the attacks she was keen to host local community consultations (a common methodology utilised by Ewald to placate, recruit, gather support and/or address issues around her projects), but this was vetoed by her commissioners. It was also decided that images of the damaged banners would not be included in the book.

Towards a Promised Land was originally conceived by the art production agency Artangel to operate as a ‘prologue’ to a series of commissions culminating as The Margate Exodus. An epic film production directed by Penny Woolcock, involving a live promenade performance incorporating crowds of local residents in a contemporary retelling of the story of the biblical story of Exodus. As Ewald’s project was to operate as an announcement for a series of larger events, all hugely dependent on active public support and participation, it would appear that it was felt best to not rock the boat. All of which clearly raises the problematic issue of a funding organization’s agenda curtailing an artist’s creative autonomy.

Ewald has remarked “it doesn’t interest me to put a frame around someone else’s world”. However as an artist concerned with representation of social issues this is what she does in Towards a Promised Land. Her finger may not always be on the camera shutter, but her name is on the book spine. In blurring the boundaries of artist, educator, author, curator and collaborator, and retaining sole authorship for the work, Ewald’s production methodology is essentially a take on an artisinal model of collaborative art production. However it would be erroneous to think of Ewald’s practice as pure collaboration. For collaboration applied to photographic practice concerned with social representation filtered through a sole author, is a misnomer. ‘Real’ collaboration by an artist with his/her subjects would be collectivism or co-authorship, which is impossible outside of a partnership of peers who equally co-join in the ambition and realization of a project at every stage from its inception and invention, through to its production, dissemination and reception (as is the case in partnerships by artist-duos such as Jane and Louise Wilson or Adam Chanarin and Oliver Broomberg).

As an artist myself, engaged with similar conceptual and methodological concerns to those discussed in this review, there is an uncomfortable feeling of critiquing the foundations of my own practice. The incisive question on community collaborative art practice once asked by the American critic Patricia C. Phillips resounds: “Does it succeed because good intentions are irreproachable?” I know first hand that a large part of the difficulty of collaboration in photographic practice concerned with social representation, is about authorship and the potential pitfall of paternalism. For regardless of how much more involved the subject is ‘allowed’ to become in the construction of their own representation, authorship can only be filtered through the singular voice of the artist. The unequal power relations located inside/out of any photographic arrangement between photographer and subject are essentially insurmountable. Collaborative practice in its most worthy and misguided sense chases fulfillment of an unachievable ideal, that is, to put power in the hands of the powerless.

Strategies of collaboration designed to actively involve the subject in the creation of their own representation are key in attempting to understand the subject depicted, issues around representation and fundamentally the medium of photography itself. Wendy Ewald’s work provides an interesting model of a collaborative strategy that redefines the instrumentality of the photographer and the subject in order to expand the presence of the subjectivity of both in the final presentation. In the end Towards a Promised Land offers a sophisticated presentation on migration and asylum in Margate.

Anthony Luvera