Exhibition review of Open See by Jim Goldberg at The Photographers’ Gallery

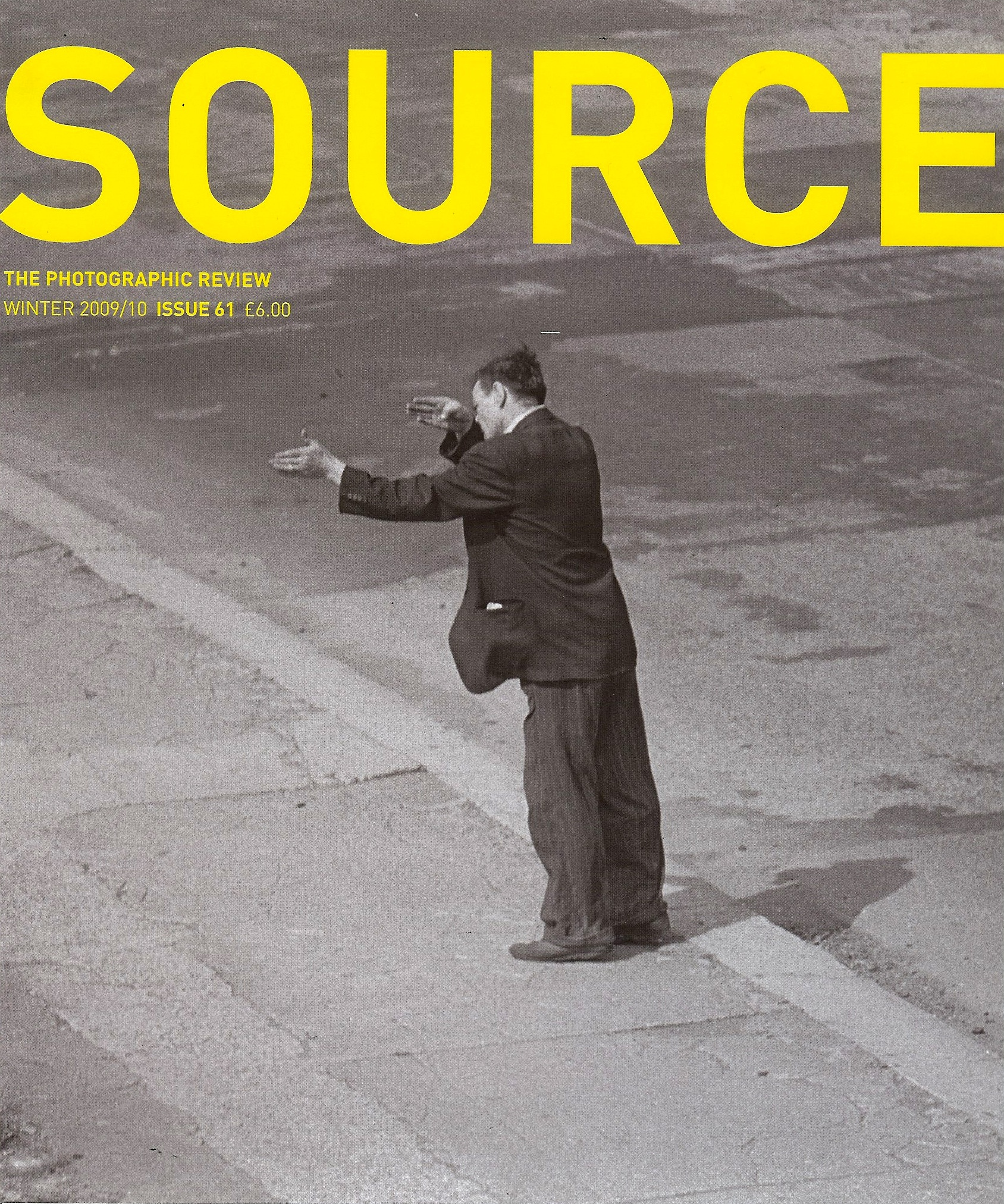

Published in Source

Winter 2009/10, Issue 61

Open See, recently on show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London, is an exhibition by Jim Goldberg about migration in Europe. The American photographer began creating this body of work in 2003 when he was commissioned to document an aspect of contemporary Greek society for the Cultural Olympiad of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games. Goldberg chose to represent refugee, immigrant and trafficked individuals, people he refers to as ‘the New Europeans’. He then travelled to the homelands of his subjects to explore the circumstances they left behind. This show is comprised of a salon-style display of over 80 photographs, a four-screen video installation and ephemera presented in a vitrine.

The volume of work presented in Open See and its arrangement in the gallery space might be seen as a topographic metaphor for the diaspora of the individuals represented in this exhibition. Large format prints depicting vast impoverished landscapes and destitute interiors appear to serve as wide ‘establishing shots’ for the multitude of Polaroid images also on show. Displayed singularly or in collage assemblages, these Polaroids often feature drawings and handwriting in a variety of languages inscribed directly on to the prints by Goldberg’s subjects and their translators.

There is a focus in many of the images on the damaged bodies of Goldberg’s subjects – scars, disfigurements, symptoms of ill-health or marks of torture. The accompanying texts convey a range of information about the outlook and circumstances of the individual, from abbreviated accounts of abject situations they have endured, to more elliptical observations about their living environments and their hopes and aspirations for the future. In Mr. Ndiho Monozande, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2008 a man shows the scars on his back from gunshot wounds. His caption states; ‘The war came and the rebels massacred my whole village and my family (my wife and 8 children) I was shot so many times I do not know how I survived. I often dream about armed men hunting me down or of my family being alive – but when I wake up I am alone and terrified. I want to escape to another country where I will be safe.’

The use of Polaroids in Open See – objects usually disregarded as a by-product of the photographic process – underscores the dialogical encounter between Goldberg and his subjects. The incorporation of the subjects’ writing and mark-making resembles a form of the photo-elicitation work of ethnographic field studies, whereby a researcher uses photographs to assemble information from an informant about their lives. By inviting his subjects to write directly on to the prints Goldberg is extending the traditional paradigm of the photographer / subject relationship, apparently providing a greater degree of subject agency. However the terms of this invitation are not made clear in the exhibition and looking at the stylistics across the body of work there appears to be a moderation of the aesthetics. This would be derived in part from decisions made in regards to the materials provided for use by Goldberg’s subjects – such as the type of pen and ink colour – but may also extend to where in the pictorial arrangement individuals were invited to inscribe their text.

The lack of transcriptions for the majority of the written material presented in Open See renders much of the information incomprehensible to English speakers. The use of non-English texts and the sporadic inclusion of translations suffuses the exhibition with a sense of frustration analogous to the experience of a non-native speaker attempting to communicate in a foreign country. The effect of this however may prioritise a response based primarily on the aesthetic surface of the works, leveraging a celebration of the artistic prowess of Goldberg over a consideration of the circumstances of the individuals represented. The lack of specific contextual information about the many and varied cultural, economic, social and political contexts relevant to each individual represented negates a holistic understanding of the forces, systems, conflicts and organisations that shape their position in the world.

The four-screen video installation screens a montage of what Goldberg refers to as ‘field recordings’ on loop. In one of these short scenes a dishevelled-looking man is trailed through an impoverished neighbourhood apparently unaware of being recorded. The subject then appears to notice the presence of the camera, confronts the artist and the footage abruptly ends. In another vignette Goldberg’s camera lingers on a woman appearing to partake in a face-to-camera interview. However all but one of these recordings are presented with the soundtrack suppressed, so what is actually happening between Goldberg and his subjects is never fully explained. The only sequence screened with volume is a recording of a group of children chanting at Goldberg’s camera, ‘white man, white man, white man…’ The children’s chorus intermittently punctures the silence of the gallery space and may be interpreted as a self-reflexive proclamation by the photographer of his position in the inside/out division of this documentary project.

The quasi-ethnographic aesthetics of Open See appear to promote a reading of the work as an ‘authentic’ depiction of the individuals represented but to view the contributions of Goldberg’s subjects as direct or unmediated would be problematic. There are also questions that could be asked regarding the subjects’ consent, and comprehension of Goldberg’s use of the co-produced material, particularly in light of the artist’s commercial gallery practice. Ultimately however, the narratives that thread through Open See are often very moving and provide a compelling take on the experiences of some of those caught in the ebb of global migration at the beginning of the 21st century.

Anthony Luvera