Published in Source

Spring 2008, Issue 54

Anthony Luvera examines a number of projects in which artists have used children’s photographs and the challenges that this work presents.

When considering practices that use photographs made by other people, it is not enough to only consider what is in the image. It must be also asked, what does the artist do with the photograph? As an artist who works with other people’s images myself, I am aware that the practice of generating and handling other people’s photographs is always a multifaceted process of dialogue, exchange, compromise and trust, and the many other nuanced complexities that cast personal relationships. Any outline of a collaborative, participatory or co-produced practice, particularly by an outside observer, will always unavoidably be reductive to some degree.

However, the products created by the artist as representative of the process, or as a result of the practice, circulate in their own right and as such constitute a representation of the subject/participants, answerable to a certain kind of questioning. What is the intention of the artist? How does context affect the representation of the subject/participant? What does the artist put forward as a representation of the process? How has the artist ‘framed’ the photographs for their presentation?

A number of artists and organizations in the UK are using photographs made by children. Four of these practices and their products are looked at here; Julian Germain, Patricia Azevedo and Murilo Godoy’s No Mundo Marahoso do Futebol, Anna Fox’s Made In Europe, Judy Harrison’s Come to Kingsland Market and PhotoVoice’s Voices In Exile.

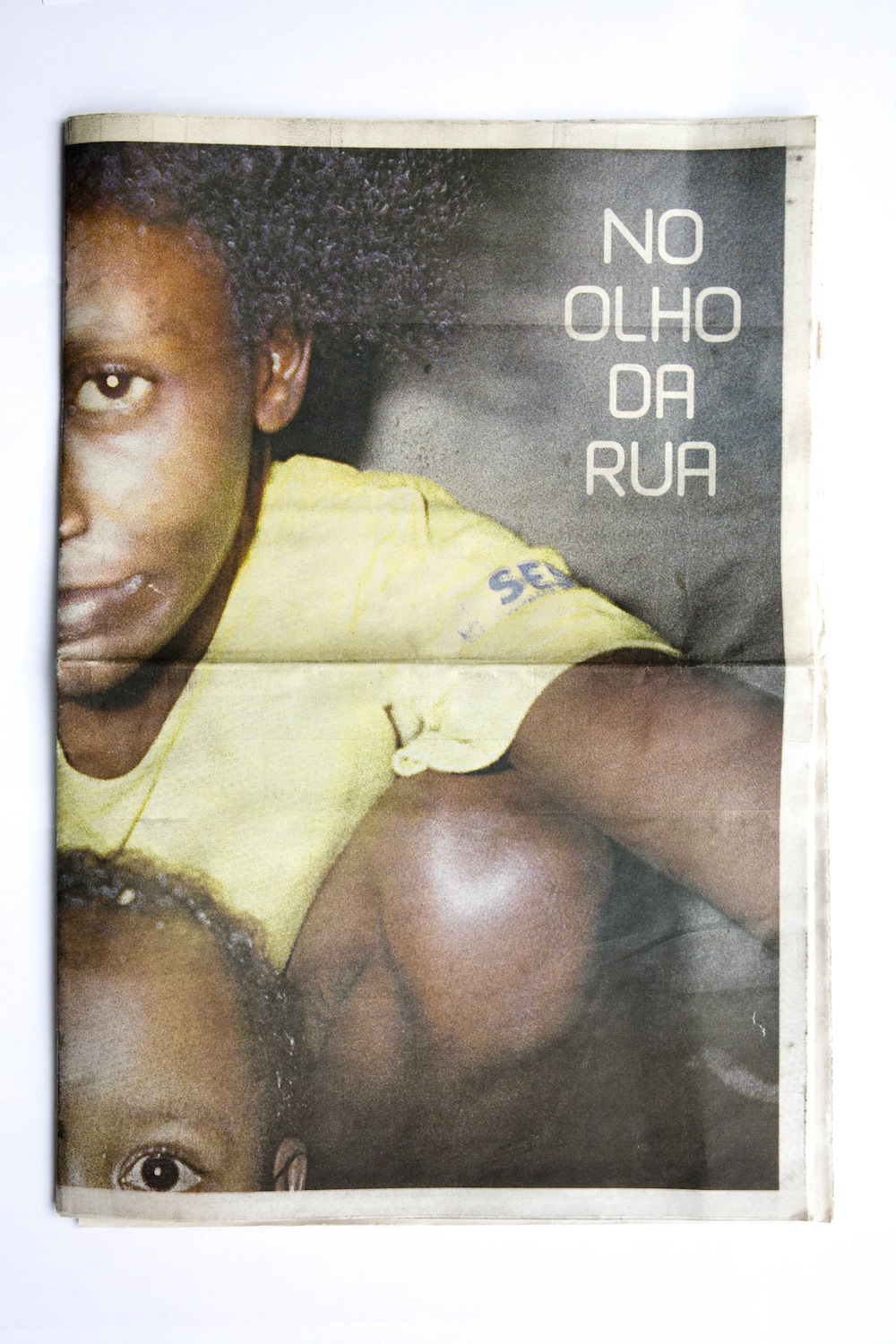

No Mundo Marahoso do Futebol

For over a decade the British photographer Julian Germain has collaborated with two Brazilian artists, Patricia Azevedo and Murilo Godoy, to facilitate a number of photography projects with children living in impoverished conditions in Portugal and Brazil. The artists have stated; “The idea is straightforward. We encourage them to explore their everyday surroundings and record how time passes in their lives through the act of making photographs. We use cheap point-and-shoot cameras loaded with colour film. We do not dwell on technical issues.”

In 1997 the three artists facilitated workshops for over 50 boys and girls of local football teams in the Cascalho favela, a shantytown on the edge of a football ground in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. They provided the children with cameras, and asked them to create photographs, paintings and writing on the theme of football and their experience of living in Cascalho. The artists then exhibited the children’s work in the Belo Horizonte Cultural Centre and produced the publication No Mundo Marahoso do Futebol. Revenue generated from the sale of this book was later contributed to the construction of a community library in Cascalho.

In the introduction to No Mundo Marahoso do Futebol, Germain, Azevedo and Godoy state that their intention for the project was to attempt to counter negative reportage photography representation of Brazilian favelas; “the initiation of the photography workshops was to a certain extent a reaction against that particular kind of representation: an attempt to offer an alternative approach, totally dependent upon the active and creative involvement of the participants… to encourage them to use photography to express their feelings.” The artists also go on to say that the children “never had the opportunity to take photographs before and as a result they were not restrained by conventional notions of what makes a good picture”.

The children’s photographs display both their love of football and the living conditions of Cascalho, with the potent intimacy achievable only through the disarming proximity of the lens of a close friend or family member. The effect of the children’s inside depiction of the favela is further emphasized by the artists’ selective use of a large number of images that, while are visually interesting, display the slip-up stylistic of amateur photography – jerky compositions, fingers in front of the lens, end-frame light leaks and poor focus. However, often the effect of the technical clumsiness of the children’s photographs diverts the viewer’s attention from what appears to be their intended subject, directly toward their abject living environment. In numerous portrait images the apparent subject of the photograph is blurred by the camera’s fixed focus lens, leading the eye to engage much more directly with the clearly depicted poverty of their surroundings. There are difficulties with considering these images as being a more authentic, unmediated or clear representation of the children’s experience of living in the favela.

The edit, sequencing and layout of the publication appears to be designed to frame the visual and written material created by the children as the product of a kind of collectivism led by the artists. There are no authorial credits on the cover of the book or captions for the children’s individual contributions. Instead a list of names is printed on an opening page and indexed at the end of the book. The names of the artists are differentiated from the participants by a larger, bold typeface. This collectivist framing is further emphasized through an edited text introducing the photographs. Attributed as a “Collective text by the children of Cascalho”, the multi-voiced introduction weaves the children’s anecdotes, facts and fantasies about football and life in the favela.

The aestheticisation of the children’s photographs, paintings and writing in the design of the book comprises a visually seductive and emotive text. However, obscuring the individual credits for the children’s contributions denies the reader a clear perception of their outlook, experience or intention, homogenizing the representation of the children. The difficulty with the lack of specific information about the individual participants and their depictions in the context of the broader social, political and cultural forces that shape their life positions is that the text might be read as a spectacularisation of their poverty.

Over the last 12 years the artists have also facilitated the creation of photographs, paintings and texts by homeless children living on the streets of Belo Horizonte. The artists are currently working on presenting this work in a number of different forms and have so far produced fly poster exhibitions and a newspaper publication. In these presentations the artists have handled the children’s images and texts in a similar way to No Mundo Marahoso do Futebol, in presenting an uncredited, aestheticised selection of visually compelling photographs attributed to a collective group of “boys and girls who live on the streets of Belo Horizonte” and Julian Germain, Patricia Azevedo and Murilo Godoy.

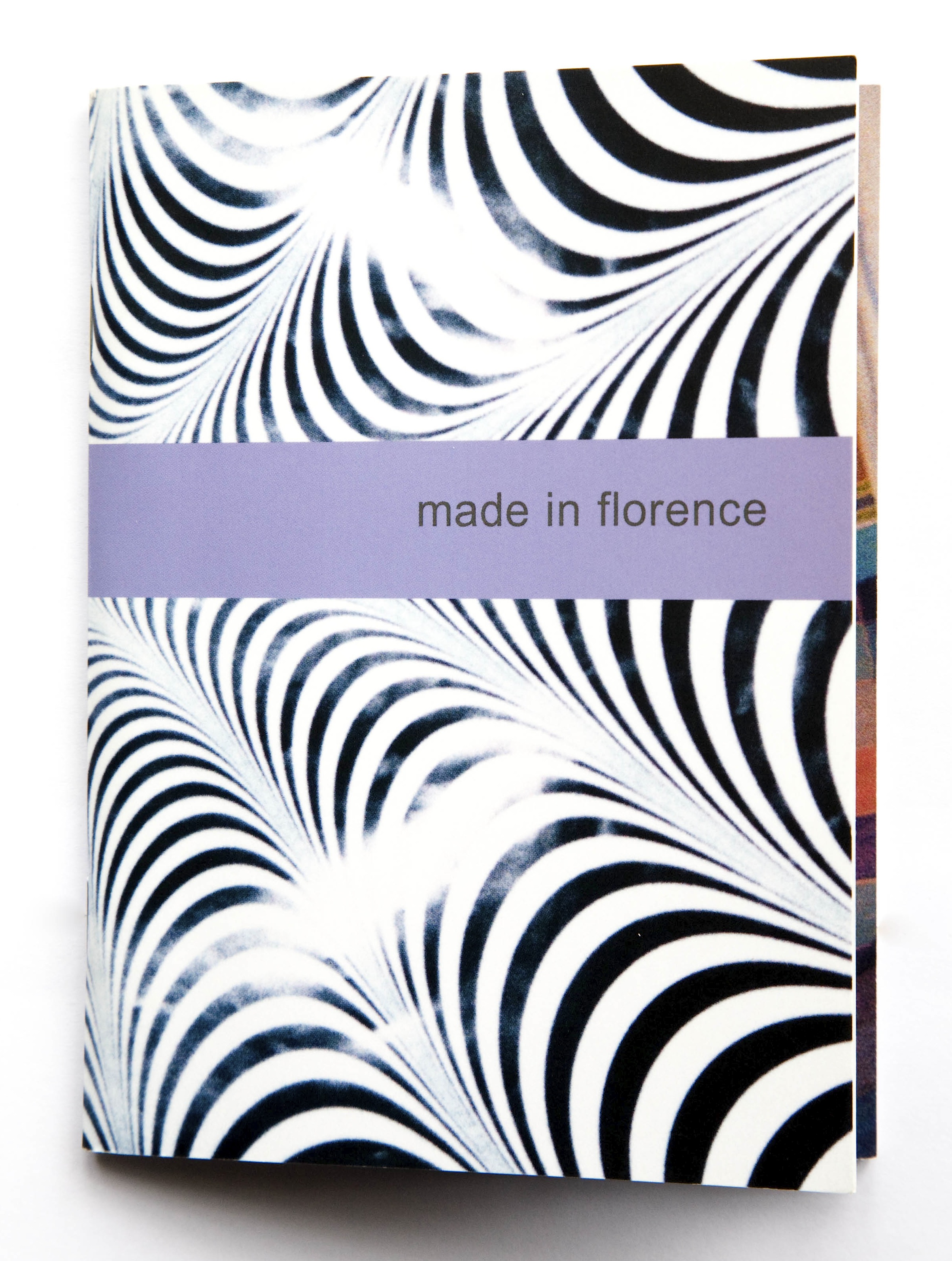

Made In Europe

Made In Europe is the collective title of a series of five booklets produced by the documentary photographer Anna Fox between 2001 and 2003. Using photographs and writing created by teenagers, Fox has stated that her intention was to “explore what happens when the camera is handed over to the subject (and) to speak about the changing nature of European life.”

Fox facilitated workshops on autobiographical photography in five schools in different cities across Europe; Gothenberg, Milton Keynes, Los Cristianos, Kaunas and Florence. Each participant was given a compact camera and a roll of film, and directed to “consider themselves as important subjects of historical inquiry, to photograph their bedroom and personal possessions and write about their hopes and fears for the future.” Follow-up workshops were also held to demonstrate an editing process. Fox then designed the booklets to present the teenagers’ photographs and writings, along with statistical information relating to the socio-economic and cultural life of their city. The opening pages of each publication state that the booklet is a collaboration. The subject/participants are credited as having created the photographs and texts, while Fox is credited with the design and editing.

The teenager’s photographs show the stuff of adolescent bedrooms through the distorted lens perspective and misplaced fixed focus of compact cameras. The images depict unmade beds, posters, desks, books, toys and outgrown artifacts from earlier childhood. The texts are presented in the individual’s own handwriting, telling of their aspirations and doubts, and anecdotes about friends, family and personal experiences.

A statement at the beginning of each booklet advises the reader; “This booklet contains private information: homes, lives, hopes and fears.” This frames the booklet as a repository for intimate details, perhaps explaining Fox’s decision not to incorporate individual credits for her subject/participants’ images or written texts. However the lack of specific credits for the photographs and texts shuffles the individual outlooks of the participants, leaving the reader to attempt to make sense of a disassociated conjunction of personal images and confessional writings, within the context of statistical snippets about a particular city.

Viewed as an inquiry in to the co-productive possibility for a documentary text, Fox might be thought of as assuming the role of an art-director or commissioning editor sending her adolescent subjects out as correspondents to report back on their domestic environments and inner world. As a consideration of the state of Europe at the turn of the millennium the booklets are best viewed together, allowing the reader to compare the different European cities. There is little to differentiate the domestic interior of Milton Keynes with that of Kaunas. However the similarities in the children’s images from different cities might be less to do with the dissolution of European borders and more to do with the tentacle reach of global consumerism, or perhaps this is the same thing.

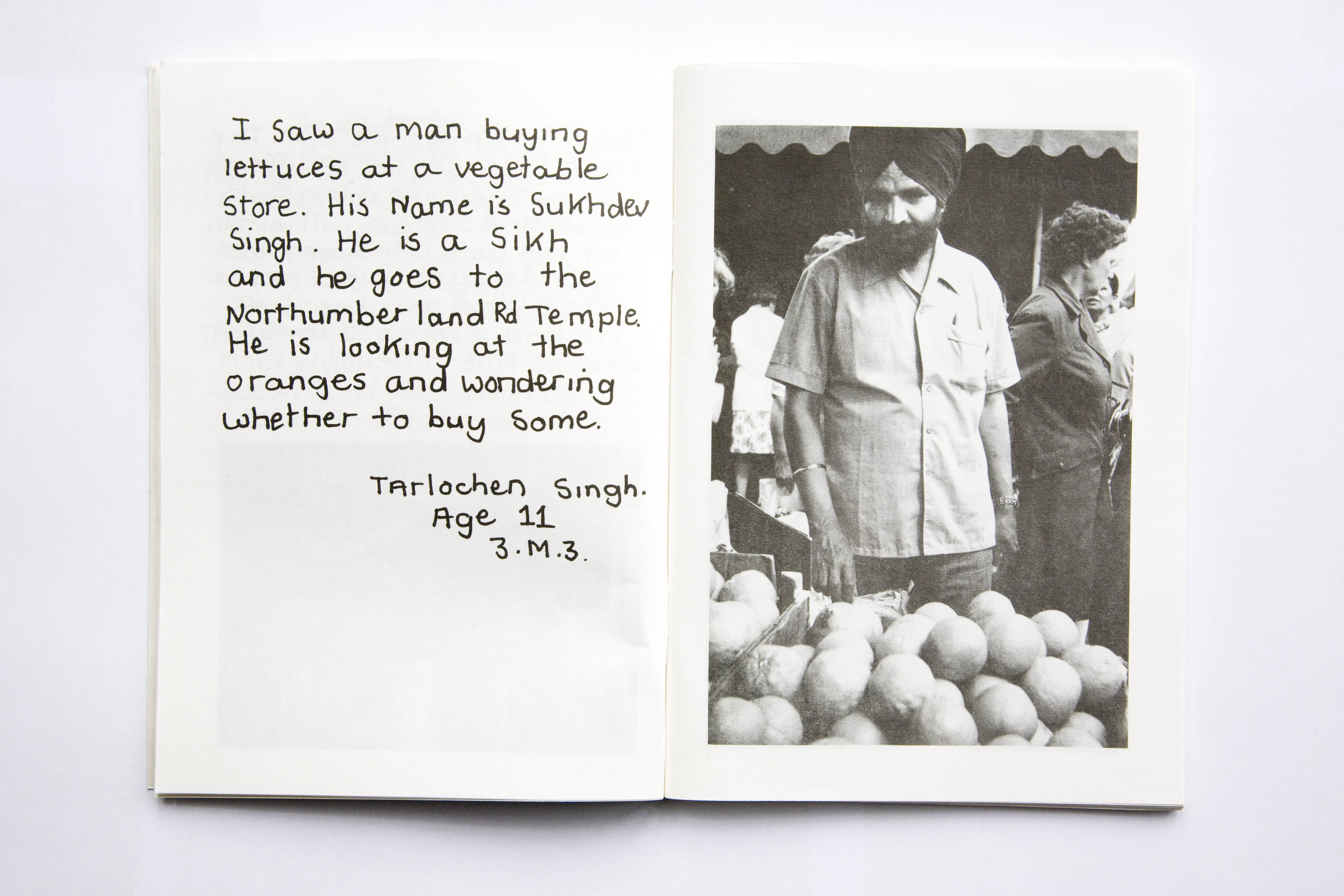

Come to Kingsland Market

“I was very interested in using photography within a social context beyond simply as an aesthetic medium… in connecting language development in education both as a learning aid and as a representational tool” – Judy Harrison

In 1977 the photographer Judy Harrison was awarded a Fellowship by the University of Southampton Photographic Gallery (now the John Hansard Gallery) to develop her photographic practice and to work with children living in Southampton. She approached a number of schools to inquire if they would be interested in using photography in their classrooms. One of the schools, Mount Pleasant Middle School, had recently begun producing hand drawn reading books and teaching aids in attempt to provide culturally relevant representations for the school’s 96% ethnic minority student population; multi-racial educational resources were virtually non-existent in the late 1970’s. Harrison proposed to run a project to teach the children how to use 35mm cameras and a black and white darkroom, in order to facilitate their production of their own visual learning resources and books for use in the classroom.

The cover of Come to Kingsland Market features a group portrait of 8 children, who are identified as the producers of the book on the opening page. The publication contains black and white images of the traders, produce and customers of Kingsland Market in Southampton, photographed and developed by the children. The images are accompanied by short handwritten texts by the individuals narrating the details and actions depicted in the photographs. A brief introduction by Harrison states “this book is a result of a children’s photography project organized by Mount Pleasant Middle School and Judy Harrison… The book is hoped to be of use with children learning English as a second language.” The publication was widely distributed to local libraries, schools, colleges, and adult further education centres for use as a learning resource.

All of the photographs in Come to Kingsland Market display a high degree of conventional technical aptitude. They are well exposed, compositionally balanced and the majority of the children’s subjects engage directly with the camera, suggesting that the child held a degree of confidence in using the equipment and relating to their subject to spend time to expose the image. The texts are written in the first person narrative voice of the child and are often injected with personal information and supplementary questions, “Why do ladies like to have net curtains at their windows?” – Corinne Davidson. Many of the children’s image and text contributions refer directly to their own cultural experiences. There are Indian recipes for ‘gobi’ or cauliflower, instructions on how to wear a sari and information about the Muslim festival of Eid.

The publication has been constructed in such a way as to foreground the subjectivity of the children, through a combination of their photographs, handwritten statements and signatures. There is minimal contextualization and virtually no interpretation of the children images and texts, and Harrison’s own authorial or facilitatory role is positioned as secondary.

At the end of the Fellowship, Harrison formalized her work with photography at the school to establish the Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop (MPPW) in order to continue to facilitate photographic learning and to work with children to assist them realize their own self-initiated projects with photography. In 1989 some of the children’s work was exhibited alongside established artists such as Zarina Bhimji in Fabled Territories, the first ever exhibition of South Asian photography in the UK, curated by Sunil Gupta. The children of MPPW also initiated, produced and distributed a magazine called Step Forward, which ran for over ten years. One of the children of the MPPW management committee, 16-year-old Meenakshi Purohit, stated in an issue Step Forward; “ We’re trying to tell people about our cultures through photographs… we’re trying to build understanding… we are the people, we are the community, and we’re doing it. It’s us looking at us and telling people, rather than someone else looking at us, telling people.”

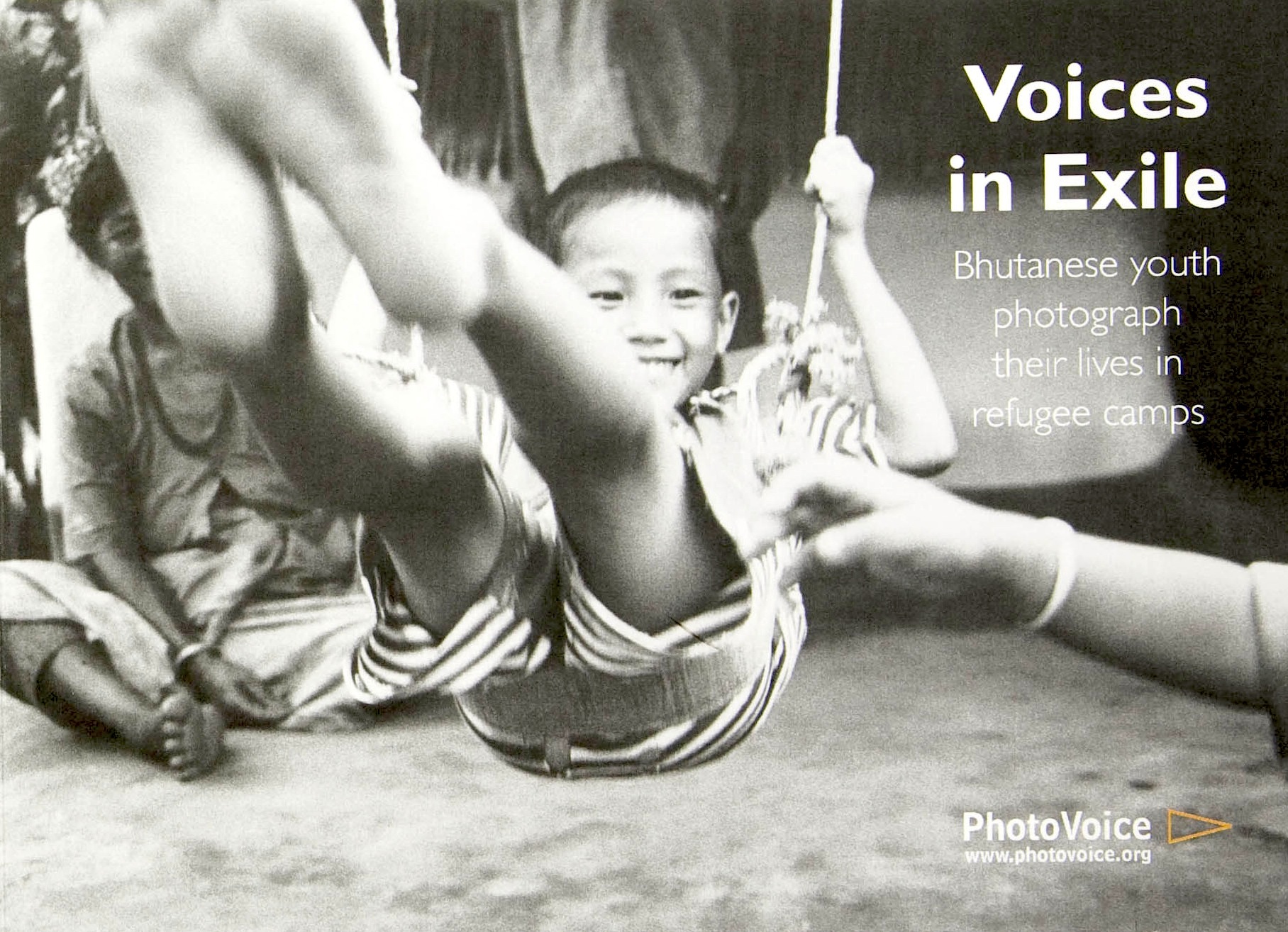

Voices in Exile

Tiffany Fairey and Anna Blackman set up the charity PhotoVoice in 2000 after undertaking postgraduate studies in social anthropology with a particular focus on participatory photography projects. The Rose Class was one of the organisation’s founding projects, established by Fairey in 1998 in the refugee camps of Bhutan in Nepal. Fairey initiated the project with the aim to “allow participants to express their hopes and fears through photography, art and writing… to build confidence, increase skills and provide a platform for the young people to communicate to their community and international audiences their stories of growing up as refugees.”

13 participants took part in Fairey’s original workshops, which over the past ten years have evolved to include around 3,000 children in a range of photographic activities; including exhibitions, a monthly newspaper and video documentaries. The project is now called The Children’s Forum and is primarily operated by a committee of young people assisted by adult mentors, and overseen by PhotoVoice.

Voices In Exile is a publication produced in 2007 by PhotoVoice using photographs created by participants of The Children’s Forum. It is part of a series of PhotoVoice booklets that present the organization’s individual projects. All of the publications in the series are produced in the charity’s in-house design style, which is slick, full color and professionally designed. The books present the children’s images and captions, along with their portraits and ‘stories’, and background information relating to their socio-political situation.

PhotoVoice negotiates with each participant of their projects to share the copyright of 10 to 15 images made by the participant. The children’s images used in Voices In Exile predominantly show the children and their community engaged in productive activities. They show a positive side to the stereotypically negative reportage of refugee feeding camps predominantly disseminated by the mainstream media; such as a young boy wearing medals holding aloft a football and trophy, a man repairing a hut, and healthy happy children collecting water. Where an image does show illness or directly focuses on the poverty of the children’s living situation, the caption provides contextual information about the actual experience of living in the camp. “An ill woman lies outside her hut. Many people get sick especially in the summer because it is so hot in the camps.” – Bishma Maya. However while the selected images provide insight into the experience of life in refugee camps and go some way to challenging negative preconceptions, it would be untrue to consider their presentation in the publication a straightforward representation of the children’s ‘voice’ or entirely representational of their actual everyday experience of living in the camp.

In the publication The PhotoVoice Manual: A guide to devising and running participatory photography projects, produced in 2007, the PhotoVoice ‘methodology’ is explained. The manual details the various priorities, techniques and components of running a PhotoVoice project; how to facilitate a process of photographic training intertwined with enabling participants “to become more conscious about how they can use the camera to ‘speak out’ about their experiences and the issues that are important to them.” These issues are usually identified by the individuals as part of the activities facilitated through the project or set by PhotoVoice’s partner organizations, or both.

Much of the language used by PhotoVoice to encase the material created by the children might be perceived as paternalistic and contradictory. “Working with positive negatives” is an example of a strap line widely used by PhotoVoice. While it is an obvious pun on photographic process, it might also be read as feeding back in to the negative labeling the organization sets out to confront. Perhaps this is indicative of the contradictory challenge of the greater charity and aid industry with which PhotoVoice is aligned, in that it essentially needs ‘negatives’, or disempowered people in order to exist.

In subverting the tropes of photojournalism, PhotoVoice might be thought of as ‘amplifying the voice’ or ‘providing a platform’ for the material created by the participants of the workshops. The incorporation of the viewpoints of the young people in the advocacy messaging disseminated by PhotoVoice and its partner organizations might constitute a subversive challenge to stereotypically negative preconceptions of the experience of life in the refugee camps. However in effect, this would largely be determined by the specific context of the placement and use of the children’s images and captions.

Considering these kinds of practices

When a practice incorporating other people’s photographs is disseminated publicly, outside the context of the group of people who created the material, it must be viewed foremost as a practice of representation, which is framed, contained or mediated in some way by the facilitating artist or organization. Not simply as the display of amateur photographs of an ‘unmediated’ reality, or a presentation from an arts participation exercise. With projects that facilitate the production of images by children or other ‘spoken for’ or disempowered individuals, consideration of issues around intention, context and representation become particularly heightened.

I know from my own experience that the ‘good intentions’ of a facilitating artist or organization and the potential positive impact of the process of undertaking this kind of practice can smokescreen any real critical rigor applied to the creation and consideration of the presented work. Good intentions will often inadvertently mask the essentially insurmountable and unequal power balance between the artist and their subject/participant. While photographs and many different kinds of photographic practices can have powerful impacts on people, the whole idea of benefits, values or outcomes inferred on to the subjects would really be best answered by the subject/participants themselves.

In writing this article I have felt a responsibility of discussing other people’s practices, and the difficulty of critiquing the foundations of my own practice. I do not want to trivialize the complexity and sophistication of any of these practices or the value of the products created by the artist or organization. These are the challenges that we all face through the practice of generating and handling photographs made by other people. Projects that redefine the roles of both the artist and the subject/participant in attempt to expand the presence of the subjectivity of both in the final presentation, can go some way to enriching a perception of those participating, what they choose to depict and the medium of photography itself.

Anthony Luvera